Glassmaking: A Jewish Tradition Part V: England Attains an Industry

Fact Paper 6-V

© Samuel Kurinsky, all rights reserved

- The Lorrainers

- A Brief Historical Background

- 1: Glassmaking devolved within a single or, at most, several related families.

- 2: Glassmaker's Security Lay in Maintaining the Secrets of Their Discipline.

- 3: Glassmakers Harbored little Fealty to the Countries Within Which They Resided.

- 4: Glassmakers Kept Their Secrets From the Indigenous People Around Them.

- Jewish Glassmakers Had To Contend With Constraints Peculiar to Their Art

- The Glassmaker's Charter

- The Eponymous Evidence

- Eponymous names of Glassmakers from Italy and Spain

- Glassmakers From the Università d'Altare, Archetypical "Tramps."

- After the Ban Against Jewish Residence in England was Lifted

- A Lost Heritage

- Notes

The Lorrainers

Most notable among the glassmakers who fled Catholic France to establish themselves in England were glassmakers from the Vôge (Vosge) district of France. They all identified themselves as Huguenots and emigrated to England en masse despite the fact that they had been granted noble status and extraordinary privileges under an official charter as Gentilshommes Verriers ("noblemen glass-makers"). The famous "Glassmaker's Charter" included four glassmaking families: Hennezel, Thietry, Thysac, and Briseval, who settled in Lorraine. By implication the charter extended a similarly lofty status to other glassmaking families in the Vôge who arrived in the region during the same period and appear to have had a common origin. Consequently they are all referred to as the "Lorrainers."

A Brief Historical Background

Glassmaking always claimed a special status among the crafts, for it was an esoteric art, practiced only by the few families privy to its ancient secrets. The roots of the family trees of glassmakers extend back to Mesopotamia where the art was born.

The process of vitrification is unique among the arts in that it was invented only once in all of human history. The process wound its way into the world over the course of four thousand years in ever-widening spirals with the descendants of the people who inherited it from their Mesopotamian progenitors, and who had passed their knowledge on to succeeding generations. To trace the origin of the glassmakers who were enticed into the forested fiefs of the Franks in the Lorraine, we must, therefore, begin by reverting back past Bohemia, the area from which it is agreed that they had come to the Lorraine. The trail leads back to Transylvania, then to Khazaria, beyond that to Persia, and still further back to Israel. The saga of that odyssey took place over several thousand long years.

The lineage of these artisans can be traced back to the eighth century B.C.E. The art of glassmaking had long disappeared from its birthplace, Mesopotamia, and was then being practiced solely among the tribes of Israel.2 The Assyrian warlord Tigleth-Pileser invaded Israel in 733-732 B.C.E., rounded up 13,150 Israelite artisans and their families, and resettled them in the Mesopotamian heartland. He immortalized his conquest by inscribing a full account of the event on a wall of his palace. The Bible confirms his account (2 Kings 15:29): "In the days of Pekah, king of Israel came Tigleth-Pileser, king of Assyria, and took Ijon, and Abel beth-maacah, and Janoah, and Kedesh, and Hazor, and Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali, and carried them captive to Assyria."

Two years after Tigleth-Pileser's death, his successor, Shalmaneser (727-722 B.C.E.), and then his successor, Sargon II, launched the campaigns that extinguished the state of Israel. Sargon recorded that 27,290 Israelites were again transported to Assyria, an event likewise substantiated in the Bible.3

The Israelites consisted of "outstanding craftsmen."4 Among the deportees were glassmakers who brought their art back to the ancient Land-of-the-Two-Rivers. Delighted with the acquisition of an exotic art, Sargon ordered a glass vessel to be made with his name boldly inscribed upon it. The alabastron of Sargon II was excavated at Nimrud and is now the proud possession of the British Museum. The vessel is unique. It is the earliest surviving vessel to have been carved and polished from a mold-produced form. It is decorated with an engraved symbolic royal lion together with the name of Sargon II, which blazes forth in cuneiform characters.5

The saga of the glassmaker's journey through the Diaspora continues with the association of their progenitors in Persia with the Khazars. The introduction of their art into Russia and Silesia (Poland) took place as the Khazar kingdom expanded to the north and west.

The Khazar empire was destroyed by the Byzantines. Despite this traumatic event, remnants of the Khazar society still remained The Spanish Ambassador to Otto the Great, a Jew named Ibrahim Ibn Jakub, reported as late as 973 that the Khazars were still flourishing.6 Nonetheless, after the conquest of the Khazars by the Byzantines, ravaged by the Rus tribes and suffering under Byzantine domination, an exodus of Jewish artisans was underway. Many moved northwestward into Silesia, where Jews from northern Europe were finding refuge among the Polish princes who extended extraordinary privileges as enticements for bringing their arts and industries into their realm. Others fled into Transylvania, within present-day Bulgaria, Hungary and Rumania. Many moved further west when Bohemian noblemen gave employment to the glassmakers among these refugees.7

The Jews of Khazaria brought Mesopotamian styles and motifs into the Danube basin. They combined with and added spice to the designs of ware being produced in the region by Jews who had fled from Byzantia itself. "One school of Hungarian archaeologists maintains that the tenth-century gold and silver-smiths working in Hungary were actually Khazars.8

The fact is that glassmaking appeared within every culture independently of the stage of development of that culture's other arts, for it was always introduced by immigrants such as the Lorrainers. This historical anomaly endured through the ages because of the peculiar cultural attributes of the glassmakers.

1: Glassmaking devolved within a single or, at most, several related families.

The close and ancient familial relationships among the Lorrainers bear out this precept. "It seems," wrote Gabriel LaDaique, a prestigious French historian of the region, "that the glassmakers of the Vôge, in the charter, originated from Bohemia, and were all of one common stock (that is what the resemblance of the branches of the family to one another leads one to believe)."9 The ultimate provenance of such "common stock," would of necessity have been the Near East.

LaDaique goes on to explain that at the time the noble hierarchy of the Lorraine had close ties with the hierarchy of Bohemia, and were under little French influence. The Norman crusaders who had brought glassmakers back from Palestine, would under no circumstance share these artisans with their rivals. Bohemia, however, harbored glassmakers who had fled west into Transylvania when the Byzantines destroyed the Khazar empire.10 The strong family, commercial and political ties of the Ducal hierarchy of the Lorraine with that of Bohemia explains the arrival of glassmakers from Bohemia at the end of the 14th or beginning of the 15th century.11

2: Glassmaker's Security Lay in Maintaining the Secrets of Their Discipline.

Glassware was always in high demand at the upper levels of society. For four thousand years glassmakers survived because only they were able to supply that demand..

Centuries earlier, St. Jerome complained that "Semitic artisans, mosaicists and sculptors are every-where." The saint cited glassmaking as one of the trades "by which the Semites captured the Roman world."12 The humiliating dependence of the Roman world on "Semitic" artisans impelled the church to launch a campaign to convert or displace the stiff-necked "Orientals."

Artisan's guilds were formed and put under the patronage of Christian saints. Conversion was required to join the guilds. Conversion was, however, unevenly enforced because no substitutes existed for certain skilled artisans. Outstanding among them were the glassmakers, for they were alone in the art. Jewish glassmakers were consequently given conspicuous exemption from conversion as a condition for continuing their art.

In Cologne... where the guilds succeeded in ultimately barring Jews from almost all of industrial occupations, they still allowed them to become glaziers, probably because no other qualified personnel was available.12

3: Glassmakers Harbored little Fealty to the Countries Within Which They Resided.

The art of glassmaking nonetheless declined to virtual extinction in central and western Europe during the Dark Ages after the exodus of the Jews. For many centuries the art of glassmaking was practiced sporadically on a primitive level until the Crusader Roger II invaded the rival Christian Byzantine empire and brought Jewish silkworkers and glassmakers back to his fief in southern Italy and Sicily. The Norman crusaders likewise brought glassmakers back from Palestine to France.

It is not surprising that inasmuch as glassmakers were never of indigenous origin, that the patriotism of glassmakers was typically confined to their art and to the community of glassmakers at large.

4: Glassmakers Kept Their Secrets From the Indigenous People Around Them.

No matter where in the world glassmakers found themselves, sharing their art with or marrying an "outsider" was deemed treason to the trade and a betrayal of the glassmaking community. "Outsiders" were understood to include their indigenous neighbors. In contrast, all glassmakers freely shared their art and intermarried with their counterparts in and of alien lands, who were universally accepted as part of their own extended family.

This was true of the Lorrainers, The practice of intermarriage only between glassmaker's families was carried forward into England. The names became anglicized, but marriage practice continued along ancient lines to a late period. It mattered not a whit whether the families of the couple came from the same country. It sufficed that both parties were legitimately scions of glassmaking families.

An interesting case in point was the marriage of a Tittery with a Rogers. What more English-sounding names can be conjured up?

The name Tittery, however, is an anglicisation of "Thietry," the name under which the family had emigrated to England. According to LaDaique, there is solid evidence that "Thietry," one of the four families cited in the Glassmaker's Charter, originated from the Hebrew biblical name Mathias. In the Lorraine "there was, in fact a large [related] glassmaking family of that name [Mathias]."13

The Tittery daughters intermarried with members of the Rogers family in the Stourbridge area. The Rogers were glassmakers descended from John Roja, obviously of Sephardic descent whose family name had become properly anglicized to "Rogers."14

Such intermarriages between families whose only cultural tie was their trade, were considered not only acceptable but normal.

Jewish Glassmakers Had To Contend With Constraints Peculiar to Their Art

Glassmakers were entirely dependant on wood from forests on the estates of the church or of feudal lords. They were obliged to work and live in or near those forests. In addition, the main market for glassware was not among the Jews. The fate of glassmakers hinged on the good-will of the Christian hierarchy, ecclesiastic or secular. Their ability to operate generally depended on concealing their religion.

In Bohemia, the Lorrainer's antecedents passed as Catholic. Subsequently they assumed another pragmatic allegiance, for no sooner than it became feasible, they all professed themselves to be Huguenots, thus avoiding the strictures of the church. When persecuted as Huguenots, they took advantage of the invitation to bring their art England. They came at a time when the Jews were banned from England. Many immigrant glassmakers took advantage of the English desperate attempts to acquire their art. As was seen in the precedent Fact Paper 6-I, disdaining the cover of a Christian religion, these glassmakers registered as being "of no church!" Therein lies the finale of an extraordinary odyssey of glassmakers through the Diaspora, from Israel into Persia, from Persia into Khazaria (Russia), from Russia into Transylvania, from Transylvania into Bohemia, from Bohemia into France, and finally from France into England.

The Glassmaker's Charter

The phrase, gentilshommes verriers, was originally intended to apply to the aristocrats who hosted the glassmakers on their forested fiefs. It was the only commercial occupation other than agriculture in which a noblemen could indulge without compromising his noble status. That is not to say that a nobleman would ever sweat at the furnace. God Forbid! Manual labor was no less disdained by the French aristocrats than it had been by the Romans, Greeks, and Persians overlords before them. No French nobleman would consider indulging in such a lowly occupation except as a consumer of its products. Hosting a glassmaking industry became the sole exception to the otherwise strictly observed social restraint. It was the only industry other than agriculture that a nobleman was legally permitted to sponsor and promote as a business.

Eventually a form of nobility came to apply to the glassmaking roturiers, the sweating gaffers themselves because of the unique and exalted nature of their product. Records show that a quasi-noble status was conferred upon glassmakers as early as 1369, when Duke John I of Lorraine, induced "foreign" glassmakers into his realm by issuing Letters of Privilege that granted the foreigners extraordinary privileges and liberties for accepting his hospitality. The "Letters of Privilege" were codified and expanded in 1448 by King Rene, and were renewed with ceremony by his son John of Lorraine in 1469.15 The extraordinary privileges granted by John of Calabra to the makers of grande verre in the forest of Darney, became famous as The Glassmaker's Charter. The charter begins with a definitive opening paragraph:

Jehan, son of the King of Jerusalem, Aragon and Sicily...Duke of Calabria and Lorraine.... [decree that the] glassmakers, working at the glassworks in the woods and forest of his highness..., are and must be privileged, and enjoy divers good rights, liberties, franchises, and prerogatives which they and their predecessors enjoyed and always used, and are held and reputed in such franchises as chevaliers, esquires, and noblemen of the Duchy of Lorraine...15

The phrase: "prerogatives which they and their predecessors enjoyed and always used" is of particular interest. The charter recalls the extraordinary privileges granted Jews by the Polish nobility to entice them to bring their industrial and commercial expertise into their backward fiefs. King Boleslav the Pious issued a charter in 1264 that became a model for securing Jewish freedom of opportunity and security from molestation. The terms were reconfirmed and extended by Casimir the Great in 1354, under the influence of his mistress Esther, described as a ravishing beauty. King Stephen Bathory (1575-1586) granted the Jews the right to form a parliament of their own, creating a virtual state-within-a-state. The privileges granted were similar to those of the Glassmaker's Charter.

A long list of truly remarkable privileges follow the opening paragraph of the lengthy document. The glassmakers were exempted from all income and other taxes and their dwelling and glassworks were to be rent-free. They were exempted from military service and from the ususal obligation to provide fodder for their liege-lord's cavalry. They were granted the right to erect their own mill

for grinding their corn; to hunt "black or tan" big game with dogs and hunting harness "wherever they wish without reprimand; to catch fish with nets and fishing tackles; to

freely cut down an unlimited number of trees from the royal forests for building their homes or for fueling their furnaces; to harvest the indispensable herbs and ferns whose ashes they needed for making glass; to make glass of whatever color they wish and "shall be free to have it transported and sold in all his highness's land, wherever they desire." The statutes even permitted each of the four families to keep up to 25 pigs [!] "for their own profit." In consideration of these benefits the "sum of six small florins are to be paid in two annual installments."

In 1597 a decree was passed in Paris to officially declare that a nobleman did not forfeit his nobility by engaging in the trade of glassmaking. Being noble by birth, and no longer in dread of the law of forfeiture, the Gentilshommes Verriers, in consideration of certain dues, delivered up their forests to the verriers roturiers. Sydney Grazebrook, a nineteenth century researcher of the genealogy of the "Noble families of Henzey, Tittery, and Tyzack," stated it concisely: "Glass-making is a noble art, and those that practice it are noble."17

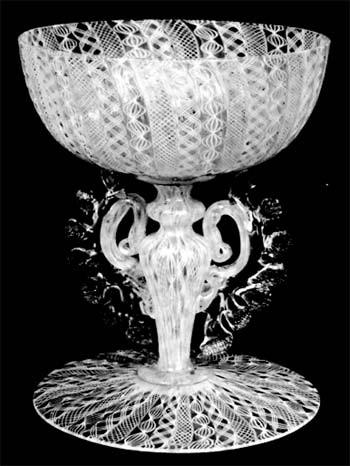

In Italy the same nobile status was granted to the practitioners of the art of glassmaking by Cosimo de Medici, who fervently sought to have furnaces installed in the gardens back of the Pitti Palace! He pleaded for masters from Venice to practice their "magnificent art" under his benevolent patronage.in Florence so that vitric masterpieces would enhance the Medici environment along with the masterpieces of such artists as Michelangelo Buanarroti and Leonardo da Vinci. Cosimo was denied the glassmasters, but after long-drawn-out negotiations, after guaranteeing to maintain the secrecy of the processes, after agreeing to a bribe of a boatload of barilla (soda from Spain), and with a persistent application of Ducal power, Cosimo finally prevailed, and succeeded in obtaining permission from the influential Venetian glassmaker's guild to install and operate glassmaking furnaces on the grounds of his grand palace in plain view from its windows.

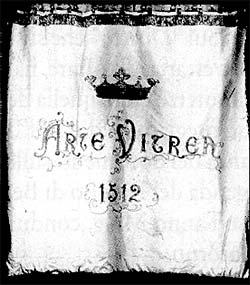

In the town of Altare in northwest Italy a community of glassmakers likewise enjoyed nobile status, granted them by the Marquise de Montferrato. The Crusader progenitors of the nobleman had brought their forefathers from Palestine to his fief in Piedmont. The community was granted autonomy, but was obliged to continue as Christian after statutes were imposed in 1512 officially tying the community to Christian faith and ritual.

Nonetheless, they continued to refer to themselves as the Università d'Altare. The term "Università" was typically applied to a Jewish community or at times to a group of "foreign artisans."17A

The Eponymous Evidence

The names of the "noble" glassmaking families, have nebulous Germanic roots, but are remarkably eponymous to sites along the route of the exodus of the Jews from Khazaria to Transylvania. The Judaic practice of assuming the name of a town or region from which they stemmed allows us to trace the migratory route with near perfection. The names not only of the four families cited in the charter but also those of all the associated glassmaking families of the Vosge provide a substantial picture of a remarkable odyssey through the Diaspora. The pervasiveness of these definitive eponyms makes manifest the only cohesive lineage that has been assembled, supports the scant but surviving documentary evidence, and makes evident the common provenance of the families.

LaDaique lists the variations of the names, stopping to note once more that the four families cited in the charter, according to a persistent tradition, were, in fact, members of one extended family. Their different family names were merely personal names altered during their passage through the Diaspora. He states that Tisza, the name of a river and valley in Transylvania, is doubtless the origin of the Tyzacks, one of the four families.

The evidence that LaDaique laid out in France was confirmed and substantiated by the equally prestigious English glass historian, D. R. Guttery. The first Lorrainer to establish himself in Stourbridge, England, Guttery notes, was Paul Tyzack, "Master of the art, feat, and mystery of broad-glass making." "Noble as the Tyzacks were," wryly comments Guttery, "[The] du Thisacks, gentilhommes verrieres... had been tramps from the early fifteenth century when they left the woods of Bohemia and began their long trek to Darney Forest in the Vosges." They were drawn to the Vosges by the privileges granted them in the famous glassmaking charter, which granted glassmakers quasi-noble (gentilshommes) status, but their decision to move into the area was also dictated by the availability of wood. "When their hungry fires had burned through one woods they moved to another. The Vosges forests promised an inexhaustible supply of cleft billets they tossed into their furnaces, not only for themselves, but also for the Henzeys (de Hennezel) and the Titterys (de Thietry), their closest kinsmen and, like them, tramps."18

A branch of the Hennezel family settled in the forest of Darney near Nancy where they worked together and inter-married with another family of the Vôge, Brasso. It cannot be merely a coincidence that there is, in fact, a town, Brasso (Hungarian: Brasho, Latin Brassovium), nested in a narrow valley in the mountains of Transylvania. The town itself is, in fact, represented by a dynasty of glassworkers whose history stems back to the time of the Khazars in that area.

Furthermore, the names of the glassmaking families associated with the Brassos, Briseval and Bysevale, derive from composites of the phrase "Valley of Brasso." These names appear in numerous glassmaking annals. The earliest reference to these families appears in the Charter of 1448 as Pierre Byseval, son of Jehan; one or both of whom must have established the glassworks called Jehan Bysevale. Thus another of the four families of the Glassmaker's Charter is linked to glassmakers of Transylvania whose history goes back to the influx of artisans from Khazaria.

Later, in England, an Ingram Brasso worked in the Weald where he had four of his children baptized between 1604 and 1608.19

An enigmatic, and perhaps coincidental variant. Briseval, appears as Bisval, alias Briseverre meaning " broken glass." LaDaique proposes that "A clue to its origin is provided by a document concerning a glasshouse at Glaserhau... Briseverre seems a reasonable translation of glaserhau." The glass works is the very first recorded such enterprise in Slovakia, founded by the glassmaster Peter Glaser, who came with his family from Transylvania in the year 1359 at the request of the sovereign of Bohemia. Glaser translates to "Glassworker" in old German, which became the Yiddish language. "Glaser" is recognized as a generically Jewish name to the present day. [Italics added]20

This event preceded the invitation of Duke John I of Lorraine to glassmakers from eastern Europe by ten years and the codification of the Letters of Privilege by King Rene by almost a century. The Glaser family was a major factor in the spread of the glassmaking art throughout Central Europe. "Another contract, signed in 1406 by the two councillors of Fribough, Switzerland, authorized 'Franciscus Glaser, who had cone from Glattow in Bohemia' to set up the glassworks 'of Gugginberg' in the canton of Berne."21

Anita Engles, author of the series "Readings in Glass History," has compiled a long list of names that makes the Transylvanian connection clear. For example:

Closely associated with the leading Lorraine families were the Bongars... In the Weald, where the Lorrainers made their first home in England, the death is recorded in 1615 of Joan, daughter to Venns, alias Ben Bungar. Venns is a tribe of Bulgars between the Elbe and The Oder-Bobar rivers, the Wends, who are now known as the Serbs. We have Bataser Wennd who was working in Germany in the18th C., and the firm of Ensell Wendt & Co., 19th C., USA.

The Wends are also known as the Polaben, Po meaning On and Labe meaning the Elbe. A Guilliame Polabbe was making stained glass windows in Orleans in 1496 and Jean Labbe was doing the same in 1593.

The Bongars came from the area of Transylvania occupied by a tribe of the same name with whom the Jewish Khazars were allied. They moved first into Bohemia with the progenitors of the Hennezells after the Khazars were vanquished by the Byzantines Thomas and Balthazar Hennezel and four other Lorrainers arrived in Alford in 1568, having escaped from the massacres of 1562. They were followed by Jean and Pierre Bongard (Bongar) the first of a dynasty of glassmakers whose descendant, Isaac Bongar, was to play a vital role in spurring the English glassmaking industry to new heights.

The Bongars were first represented in England by glassmakers who came from Normandy, Jean and Pierre Bongar, and their descendant, Isaac Bongar.22 Isaac bought up forest lands and his establishment grew to become one of two firms accused of controlling all of Sussex manufacturing by London glaziers.23 The Oldwinsford Parish register of 1613 lists the names of two "foreign" glassmakers, the earliest recorded in the district, One of these "foreigners" was Danyell Bongar, and he was buried there in 1615.24

The name Venn likewise derives from the land of the "Venedi" tribe of Transylvania. The death of a daughter of the Venns is recorded in the Weald in the very same year. An Anthony Voydyn was a glassmaker buried in Gloucestershire in 1601.25

A Tubal Crissom was associated with the Henzeys and the Tisacks at Newcastle-on-Thyne in 1631. The distinctly Hebrew "Tubal" is followed by a variation of the town of Crissa, "an ancient coastal city in the vicinity of Delphi," which Benjamin of Tudela visited on his way to Corinth."26 Thus another branch of the route of the glassmakers becomes evident, this time leading from Byzantia. As noted above, the styles of the glassware of the Danube basin was a combination of the Persian and Byzantine influences. The analysis of both types of glassware, however, shows that they were the same as precedent Near Eastern glass.

Eponymous names of Glassmakers from Italy and Spain

Glassmakers from other regions responsible for the founding of the glassmaking industry in England likewise bore names that betray the origins of their bearers, even in their anglicized forms. In Fact Paper 6-I, Jacob Verzelini was shown to have been born in Venice, from which glassmaking center he went to Vercelli, a town near Altare where Jacob probably worked before his emigration to England. Vercelli was one of the towns of north-central Italy from which the Jews were driven at the end of the 16th century Nearby Vercelli and closer to the glassmaking Università d'Altare was the town of Caluso. An Angelo Barcaluso worked in London in 1618, and was referred to as a "glassmaker born in the city of Venice under the Duke."27 The name "Barcaluso" is of common and distinctly Hebrew construction, since Bar means "from" in Hebrew, and the name translates to "Angelo from Caluso." Thus, like Verzelini, the name together with the records tell us that, born and raised in Venice, Angelo moved to a town near Altare where he was probably given employment until it was possible for him to make his way across France and the Netherlands, to finally settle in England.

Metreves was another glassmaking family that abandoned Venice to wander the Diaspora. Whereas Bar translated to "from" in Hebrew, Me translates to "of" in that language. Me-Treves, therefore, identifies the bearers as Jews or descendants of Jews of the town of Treves in France. Treves was a major center of both Jewish and glassmaking activity in the Roman period, had a revival of both Jewish life and glassmaking in the Middle Ages. Its Jewish community was among those that fled over the Alps into Italy. Persecution in Italy drove them back again through France and eventually to England.

An intriguing itinerary of a member of that family can be discerned from documents concerning Dominique Metrevis, a glassmaker who worked in a glasshouse in Woodchester, England. .Dominique, being the Italian form of the Spanish name "Domingo," suggests that its bearer was or stemmed from one of the Spanish glassmakers who found refuge or work in the Università d'Altare before going to Treves, where he set down roots until his move to the Netherlands, and from whence he ended up in England! His surname marks the stopover of the family in (French) Treves. Nonetheless, the marriage records register Dominique Metrevis as "an Italian foreigner." and reveals that he came to England from Antwerp.28 Dominique married an Englishwoman, Mary Paslow in 1610.

The name Treves has become immortal through numerous members of the Treves family who were renowned throughout the world as Jews who distinguished themselves in the fields of science, literature and commerce. Vercelli (the very town from which Verzelini stemmed) was the home town of an important branch of the family. One of its outstanding members was Emilio Treves, one of the principal donors to the Università Israelitica of Vercelli, who also gave a sizeable sum for the initiation of a Christian asilo infantile, a children's school. The donation was made in honor of the tenth anniversary of the emancipation of the Jews by King Carlo Alberto in 1848. Emilio was honored by the Christian commun-ity for his generosity. In 1866 a Jewish asilo infantile was funded in Vercelli by a nephew and heir of the Vercellese philanthropist-banker, Isaiah Treves.29

The Altarese/Venetian glassmaking family who spelled their name variously as Bartolussi, Bortolossi, Bortolussi, or, as the name appears in Altare, Bertoluzzi is again a Hebraic construction (Bar Tolosa), Tolosa being the town now known as Toulouse. The family is well represented in Venice and Altare, to which town they migrated in the fifteenth century.

On March 5. 1461, a Matteo Bartoluzzi was active in Altare.30 A member of the family was among the emigres to return from the Altare area to France.

Thomas Bartholus, together with a partner Vincent Bassona, were granted permission to set up furnaces at Rouen by Henry II in 1598. He registered as being "from Mantua"albeit his name derives from the town of Bassano near Mantua!

Another indicative glassmaking family's name, Bartoletti (and its variant Bertoletti) is a name commonly found in Italian glassmaking annals which is likewise marked with both ethnicity and provenance. Bar Toletti is Hebrew for "from Toletti, or Toledo in Spain, for it originally bore the Latin name Toletum and was alternately called Toletti in Castilian." A branch of the Bartoletti family was related to the renowned Jewish-Florentine banking family Da Pisa. A Giacomo (Jacob) Bertoletti returned to Spain to become the supervisor of a glass factory in Castilla la Nueva, which in turn had been opened in 1689 by another Italian, Guglielmo Toreato, known to have previously come to Spain from the Netherlands (most probably Antwerp).31

An Altarese glassmaker Simon Bergamyn ("Simon from Bergamo") appears as a naturalized citizen in England early on in 1562. The name Simon was then employed exclusively by Jews. That Simon was of Jewish origin is reinforced by the use of a town as his family surname.

Tramps, indeed!

Many other English glassmaker's names bear the stamp of passage through the pathways the Jews took from the Near East through Khazaria, Spain, Venice, the Netherlands and Altare. Worthy of mention are Jeremiah Bague, Phillip and two Abraham Bigoes, members of one such glassmaking family (variations: Bigault, Bago, and eventually anglicized to "Bagg"!). Abraham Bigo was a partner of Paul Tyzack and Paul's nephew, Zachariah Tyzack in 1600. It is a typical example of inter-family glass family's business relationships, matched by family inter-marriages.32.

The name of the De Roja family first became "Rosso" and "Rosse" (the Italian translation of Roja meaning "red"). As was mentioned above, it eventually became anglicized to "Rogers." Occasionally the intercourse between the glassmaking families led to peculiar aliases. According to the English glass historian Guttery, members of the Tittery family appear occasionally under the alias "Roja." In 1641, for example the death of a Daniel Tittery, alias Rogers, alias Roja was recorded! The interchangeability of the names was undoubtedly a consequence of the type of intermarriages mentioned above of the Tittery (originally "Mathias") sisters to members of the Rogers (originally "Roja") family.

Some of the Roja family retained the original Spanish form. A Daniel Roja, for example was buried at Broome in 1687. A Henzey (Hennezel)and a Bague were also buried in the same cemetery between 1676 and 1680. The close relationship between the Lorrainers and the Sephardim led to their lying side by side in the English cemeteries in which they were finally put to rest.

Glassmakers From the Università d'Altare, Archetypical "Tramps."

Between 1582 and 1584, Luigi Gonzaga, Brother of Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantova and of Montferrato (where the Università d'Altare was located), and a protector of the Jews, became the Duke of Nevers. The Gonzagas were eager to develop the region. Jews from throughout the Gonzaga's realm and glassmakers from Altare established themselves anew in the area. Altarese glassmakers were among the first to take advantage of the new opportunities in the area under the Gonzagas.

Provence became a major stopping-off place from which the glassmakers of Venice and of Altare were likewise drawn to England. Many also stopped off in the Netherlands on the way. The coincidences in time and place of the migrations of glassmakers and Jews become strikingly evident along this route. Some Jews remained throughout the worst of the middle ages in Lyons, the papal center at Avignon, and in other Provencal localities where they were subjected to a periodic cycle of protection and repression. Jewish residence had ostensibly been terminated in 1501 and almost disappeared until Jews were welcomed back under the benign protection of the Gonzagas. The art of glassmaking concurrently disappeared and reappeared!

It reappeared shortly after the Gonzagas gained hegemony over Provence when two glassmakers from the Università, Giacomo and Vincenzo Saroldi founded a glasshouse in Nevers. It became "an important center of the glass industry, so much so that it became known as 'a second Murano.'"33 Nevers was the center from which glassmakers and the glassmaking industry dispersed through France.

The success of the industry in Nevers drew other Altarese glassmakers to the now congenial Provencal environment. Members of the Perrotti (or Perrotto) family were among the Jews who had enjoyed the hospitality of the Ducal palace in Mantua under a patente di familiari.34 The patente gave selected Jews the run of the palace as members of the Ducal household and other extraordinary privileges.

In 1649, the most famous glassmaking member of the Perrotto family, Bernardo Perotto, was invited by his uncle, Jean Castello (originally Castellon, indicating the family's Spanish origin) to work in Nevers. In 1662, Bernardo established his own glassworks in Orleans and revolutionized the glass industry. He developed a casting system of producing flat glass panels ("broad-glass," as contrasted with "crown glass"), for which he was granted a royal patent for the revolutionary process in 1668. Subsequently Perrotto patented formulas for making white glass (porcelaine en verre), of making red glass (rouge des Anciens). These and other significant break-throughs won Bernardo a well-deserved, permanent place in the glassmaker's hall of fame.35

A branch of the Perrotto family emigrated to England, and played an important role in the development of the Bristol and Stourbridge glassmaking industry. The Perrottos entered into a restrictive trade agreement with the "Broadglass" Stourbridge families of Henzey, Tyzack, and Batchelor, and were co-defendants in an action by an Englishman, Mansell, who attempted to break their monopoly. The event is a further example of the bond between the glassmaking Lorrainers and the Italians and the Sephardim as against "outsiders."

The family Rachetti were among the Sephardim who had sojourned in the Università d'Altare. Members of the Rachetti family followed the same route through Provence to end up in England where the family name was transformed to "Rackett"!

Members of the glassmaking Dagnia family had also won a position as Jewish familiari of the court of the Duke of Mantua.36 That the family also originated from Spain is made evident by the original Spanish spelling of the name: "Dagna." In Altare the spelling was later changed to Dagnia, the soft Spanish gna being transcribed into the Italian equivalent gnia. The earliest known allusion to the family appears on the Ligurian coast in 1480, where Guglielmo Dagna purchased soda and later shipped a load of glassware to Nice.37 In 1602 an Oduardo Dagna is recorded as a consular member of Altare, evidently the very Duardo Dagna who was granted a Patente di Familiari by the Duke of Mantua seventeen years later.

The members of the Dagnia family, consisting of a father and four sons, brought the formula for lead glass to England, and made important contributions to the English and Scotch glassmaking industries. In 1651 two sons established the first glasshouse in Bristol. Another two sons struck out in 1684 to Newcastle-on-Thyne where they founded the world-famous Closegate Glasshouse. This history is covered in detail in Fact Paper 6-III.37B Suffice it for the present purposes to note that a Benedetto Dagne was one of those who earlier had settled in Provence after it came under the hegemony of the Gonzagas. He is registered as a vetraio (glassmaker) of Nevers in 1559.

Another Altarese glassmaker who must be included as a major contributor to the English glassmaking industry was Giacomo da Costa, who brought the formula for lead ("flint") glass to his employer, Ravenscroft. Ravenscroft patented the formula and is given credit for its "invention" in most histories!

The da Costas were Sephardim who had taken refuge in the Università d"Altare, and became members of the ruling body of the community. In 1607 James Lopez da Costa won acclaim as the founder of the first Amsterdam synagogue. Other members of the da Costa family became distinguished in the highest professional, commercial, academic, medical, and banking circles. The story of Abraham da Costa, and some of the other remarkable contributions of the da Costas are detailed in HHF Fact Paper 41, The da Costas, a Remarkable Sephardic Family..

The Ferro family, originally from Venice and subsequently from Altare, became well represented in England, as did the Pisano family, one of whose female [!] antecedents, Heremia Pisano, was among the first group of glassmakers brought to England in the earlier aborted attempt to establish the industry under Edward VII.38

The family name Ferro, was, at that time a generically Judaic name in Italy, as was its counterparts Herriero in Spain, Ferriere in France, and Eisen in Germany. The Jews were strongly represented among the smiths, and names such as Gold, Goldsmith, Silversmith and their variations are generically Jewish to the present day. Similarly, the names Glass, Glaser, Glassman have carried on into contemporary times as Jewish names.

The English hunger for glass technology was continuously fed throughout the 17th century by artisans fleeing oppression on the continent, whether imposed by the Catholics or the Calvinists. Abraham, Jacob, and Benjamin Visitalia, settled into Bromsgrave in the 1650s and immediately integrated into English society. By 1665 Abraham "Wistolia" was appointed to the office of Overseer of the Poor. In 1656, Jacob Visitalia married an Englishwoman, Katherine Hawker.

The glassmaking industry was developed in Ireland in the early 17th century by Abraham Bigoe and the Henzeys, who had followed a glassmakerd called "Davy the Frenchman" into the Emerald Island. Davy was "working a [glasshouse for the Earl of Cork" in 1620.39 Guttery pauses to take note of the fact that the names David and Abraham are typical of the 'biblical names to which the Lorrainers were attached, Joshua, Ananias, Zacharias, Elisha, Benjamin."40 In fact, the names Samuel, Simon, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph likewise appear universally among the Lorrainers, as does Sarah and other women's names that exhibit the same propensity for Old Testament flavor. An intriguing entry is that of March 25, 1589, in which it is registered that a newborn descendant of the Henezells, Jehuditha Hensye (Jewess Hensye) was baptised in Newent, Woodchester.41

After the Ban Against Jewish Residence in England was Lifted

The Cromwellian liberalization of English law regarding Jewish residence brought about a radical change in the tenor of Jewish immigration. Jewish glassmakers came to England from the continent, this time as open, practicing members of their faith. Subterfuge was no longer aa necessity, and glassmakers openly practising Judaism rapidly integrated into the English glassmaking milieu. They were attracted to the Birmingham and Bristol areas, where the industry was thriving, and they made new and important contributions to it.

Mayer Oppenheim was among these Jewish immigrants. Born in Pressburg (then a town in Hungary), Mayer appears importantly in the annals of English glassmaking as the inventor of red (ruby) glass, for which he was granted a patent by King George II in 1755. His name appears in the Birmingham directories phonetically transcribed from the Hebrew as "Opnaim."42

Later, Mayer Oppenheim opened a second business in London, where he received a second patent for ruby (garnet) glass from George III. He still identified himself as "Mayer Oppenheim, of Birmingham in the county of Warwick.43

No less important than the rich ruby glass of Mayer Oppenheim was the invention and production of Bristol Blue by the glassmakers Lazarus and Isaac Jacobs. Lazarus Jacobs came from Frankfort-am-Main and established himself in Bristol about 1760. Fourteen years later Jacobs took over the well-known but bankrupt Perrot Glassworks. Jacob's son entered the business as a partner. In 1786 Jacob built a synagogue for the Jewish community on Temple street, the same street on which the glasshouse was located and inscribed himself under the name Eliezer ben Jacob. Lazarus Jacob died at the age of 87, and his business was taken over by his son Jacob.

"From the mass of documentary evidence which forms the main source of information on Bristol Glass, one name stands out, that of Isaac Jacobs,"43B state three chronic lers who compil ed a history of Bristol Glass. "Glass making in Bristol is invaria bly associat ed with Lazarus and Isaac Jacobs, who were among the outstan ding manufa cturers of glass in Englan d in the late 18th century and early 19th, when Isaac the son, was appointed glassmaker to George II.44 Isaac ben Lazarus elevated the name of Jacobs and that of Bristol glassmaking to new heights of fame with the production of the most elegant pieces in vibrant color, Bristol Blue, which became the generic word for the color and a byword by which their fame are perpetuated. In 1805 Isaac established a new entity, the Non-Such Flint Manufactury45 with the advertised objective to "continue manufacturing every item in the Glass line (even the most common articlesd) of that superior quality which has hitherto given him the decided preference to any other house in the kingdom."46

Isaac's performance fulfilled the prophesy of his advertisement and won many honors. About 1806 he was appointed "Glass Maker to his Majesty." In 1809 he was granted "Freedom of the City." In 1812 the family was granted a Coat-of-Arms.

The adventurous sons of Isaac brought glassware to the New World. Isaac's eldest son Joseph sailed with a "venture" of glass to Santo Dominigo, Martinique and the Barbados. Another son, Lionel, followed in Joseph's wake across the Atlantic, He is reported to have died in Spanish Town, Jamaica.47

A Lost Heritage

It was inevitable that the Jewish identity of glassmaking families became lost during several millennia of separation from the larger community, a separation occasioned by the necessity of using a Christian cover to gain access to the usufructuary use of forest wood, to avoid guild restrictions to Jews, and to maintain access to the largely Christian market. Working under the strictures of a society that proscribed the practice of Judaism outside of the Ghetto, the ethnic memories of these families inexorably faded into the fabric of the Christian cover they had assumed.

The fact remains, as was pointed out at the outset of this paper, that the process of vitrification was invented only once, and that the process wound its way into the world from generation to generation, and from country to country from the time Israelite artisans were deported to Assyria.

The Judaic heritage has long disappeared from the memories of the descendants of the Gentilshommes Verriers and their glassmaking compatriots. Ironically, the reason for their later emigration from France "Was the fact that the Lorraine glassmaking families, en Masse, had adopted Calvinist Reform, and had thus become the object of religious persecution, disabilities, and discrimination."48

The glassmakers tramped for three thousand years through the Diaspora. They mixed, married, and miscegenated, and forgot who they were and from whence they came.

SK

Notes

1: (Cover) Riccardo Calimani, The Ghetto of Venice, 1946, trans. M. Evans & Co., New York, 1987, 32; Carla Boccato, "Licenze per alcune concesse ad Ebrei del Ghetto di Venezia," La Rassegna Mensile di Israel, March-April, 1980, 106.

2: Samuel Kurinsky, The Glassmakers; An Odyssey of the Jes, New York, 1991, 129-1307.

3: 2 Kings, 17:6 See also Haym Tadmor, "The Campaigns of Sargon II of Assur." Journal of Cuneiform Studies 121 1958, 33-40.

4: H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard Un. Press, 1976, 135.

5: Harold Newman, An Illustrated Diactionary of Glass, London, 1977, 271-272.

6: S. W. Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews, vol. IV, New York, 1957, 167; Also Arthur Koestler, The Thirteenth Tribe, New York, 1976, 129.

7: This history is given in Samuel Kurinsky, The Glassmakers, An Odyssey of the Jews, 1991, ch.10, "The Khazars," pp.321-359.

8: Koestler, Ibid, quoting from G. Laslo, The Art of the Migration Period, London, 1974, 244.

9: Gabriel LaDaique, Verre et Verriers de Lorraine sous L-Ancien Regime, University of Nancy II, 1998/99, 45.

10: Samuel Kurinsky, The Glassmakers; An Odyssey of the Jews, New York, 348-9.

11: Gabriel LaDaique, idem.

12: St. Jerome, Comm. In Exekiel, xxvii, in Pat. Lat. 25, 313, "Orbe, Romano Occupato

13: Salo W. Baron, Arcadius Kahan and other contributors, ed. Nachum Gross, Economic History of the Jews, 1975, p. 40.

13: Engles, Readings in Glass History V, Jerusalem.

14: Engles, Idem,

15: Gabriel Ladaique, The Glassmakers of the Vosge, 1975, 2,3.. Anita Engles, no. 5. Ibid.

16: As given by Anita Engles, "The Glassmakers Charter," Ibid., 18.

17: Sydney Grazebrook, "The Nobility of the Lorrainers, Aristocrats of Antiquity," Collections for a Genealogy of the Noble Families of Henzey, Tittery, and Tyzack, Stourbridge, 1877, iv-v.

17A: HHF Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare.

18: D. .R. Guttery, From Broadglass to Cut Crystal, London, 1956, 1.

19: EnglesIdem, citing Lippincott's Pronouncing Gazateer of the World, Philadelphia 1880.

20: G. Weiss, Ulstein Glaserbuch, Berlin, 1966, 323.

21: Engles/LaDaique, Ibid.,4.

22: Thorpe, 1924, Ibid., 64.

23: T. C. Baker, The Glassmakers, Weidenfield and Nicolson, London, 1977, 44.

24: Guttery, Ibid., 7.

25: H. J. Powell, Glassmaking in England, Budapest, 1963, 15.

26: Engles, Idem.

27: Thorpe, English Glass, London, 1935, 121.

28: Thorpe, 1935, 89.

29: Maurizio Cassetti and Giovanni Rosso, Origini e primi sviluppi degli asili infantili in Vercelli (1847-1882) Vercelli, 1987, 12, 23, 35.

30: Guido Malandra I Vetrai di Altare, Savona, 1983, 259.

31: Alice Wilson Frothingham, Spanish Glass, London, 1963, 62-63.

32: Guttery, Ibid., 73.

33: Riccardo Richebuono, "Bernardo Perrotto, geniale vetraio Altarese," Miscellanea sul vetro, issued by the Istituto per lo studio del vetro e dell'arte Vetreria, Altare, 1984, 56.

34: Archivio Statale Torino, Registro Concessione VIII, fol. 237, Feb. 5, 1621. Patente di Familiari issued in favor of the brothers Giacomo and Rocco Perotti,

35: Luigi Zecchin, "Bernardo Perrotto, vetraio altarese," Giornale Economico, Venice, 1949, Zecchin states "The history of the glassmaking industry of orleans is identified by the history of the activity of Perrotto of Perrotto of Orleans; also A Boutiller, La vererrie e les gentilshommes verrieres de Nevers, Fay et Valliere, Nevers, 1885.

36: Archivio Statale Torino, Registro Concessione VIII, fol. 201, April 27, 1619, Patente di Familiari issued in favor of the brothers Douardo and Battista Dagna.

37: Malandra, Ibid, 242, 260.

37B: Fact Paper 6-III, Glassmaking, A Jewish Tradition; Part III: Flint Glass and the Jews of Genoa

38: H. Schuermans, "Lettres sur le vetrerrie," Bulletin de la Commission Royale sur l'Arte et l'Archeologie, Brussels, 1883/1991, Letter X, bulletin XXXIX, 117.

39: Guttery, Ibid., 78.

40: Guttery, Ibid., 97.

41: T. Pape, Medieval Glassworkers in North Staffordshire, 1934.

42: Prosser, Birmingham Inventors and Inventions.

43: Cecil Roth, The Rise of Provincial Jewry, London, 1950, 33.

43B: Cleo Witt, Cyril Weeden, and Arlene Palmer Schwind, Bristol Glass, published in conjunction with the City of Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, 1950, 33.

44: Zoe Josephs, Lazarus and Isaac Jacobs of Bristol, as given by Anita Engles, ed. Readings in Glass History, No, 4, Jerusalem, 23.

45: Felix Farley, Bristol Journal, July 12, 1806.

46: Pape, Ibid., 11.

47: C. H. Walken, In the Matter of Jacobs, a Bankrupt, London, 1821.

48: Engles/LaDaique, Ibid., 14