The Judaic Origin of Venetian Glass Part II- An Industry Created by "Foreigners"

Fact Paper 29-II

© Samuel Kurinsky, all rights reserved

- Judaic Presence in the Ancient Veneto

- Venice Becomes a Sea-going Nation

- Venice Acts to Capture Judaic Enterprise

- The Padua Connection

- The Forestieri (Foreigners)

- The Ferros and the Pisanos

- Notes

Judaic Presence in the Ancient Veneto

As we have seen in HHF Fact Paper 29-I, little physical evidence of Judaic presence in the Veneto (northwestern Italy) has survived from the Roman period.1 Neither did such physical evidence survive the Dark Ages. Physical evidence of the art of glassmaking is likewise virtually absent during the latter period. A few highly indicative artifacts of both the presence of the Jews and the art of glassmaking managed to came through both periods, but we are left to reconstruct the history of the Judaic presence and of the glassmaking industry in this region of Italy by peripheral or negative references.We will first consider the question of Judaic presence in the region. Tombstones bearing inscriptions referring to a synagogue dated to the early Roman period were found in the city of Brescia. They were found in secondary use in ancient but subsequent (Christian) buildings. Yet the Judaic community of Brescia is absent from all histories. Even the Encyclopedia Judaica has no mention of it. The tombstones and a few other significant artifacts are now housed in the Museo della città of Brescia.

The history of the Judaic community of Aquileia is likewise absent despite the existence of mosaic floors of one or more synagogues underlying Christian structures in the region, and despite the uncovering of other artifacts. The floor(s) and artifacts render mute evidence of the substantial historical hiatus regarding Judaic presence. One of these floors, clearly that of an ancient synagogue, is presently housed in the "Paleo-Christian Museum" of Monastero, no more than a kilometer away from Aquileia.2

Indirect and negative references to Jewish existence during the Dark Age in the Veneto should leave no doubt that substantial numbers of Jews were to be found throughout the Veneto in the period between the devastating invasions of Alaric the Goth and Attila the Hun and the formation of the Venetian Republic. The only fact open to conjecture is the magnitude of that presence.

The repressive decrees of the Christian hierarchy following the Mongol invasions, and the respite from those acts by the decrees of Theodric the Ostrogoth, cited in Fact Paper 29-1, must be accepted as clear proofs that, indeed, a population of Jews of considerable importance existed in the Veneto. The immediate re-imposition thereafter by the church of virulent anti-Judaic statutes again makes manifest that Jews were not only present but were of substantial numbers and influence.

Some documentary facts emerge from the darkest periods before and during the formative years of the city of the lagoon. About the year 800, Charlemagne journeyed from Bergamo toward Val Camonica. He reported that well-established Jews owned impressive Castelli in the Alto Adige. These fortified villas in the hinterlands of the Veneto could not have been mere family enclaves, but must have been centers in and around which other Jews lived.3

In Verona, we are negatively apprized of Judaic presence by the actions of Raterio, the archbishop of the city in the tenth century. Raterio sought to protect the faith of his constituents by expelling resident Jews. The stated purpose was to prevent corruptive contact between the two populations. We must assume thereby that such inordinate measures would have been taken only if enough Jews were present to be of concern to the church.

Ratirio's effort failed. The crucial importance of Judaic enterprise to Verona's economy became an over-riding factor between faith and favor, and the decrees were rescinded.4 Notwithstanding that decrees of expulsion and repeal would only be instituted if enough Jews were present to be of concern, no other mention of their existence in that period is extant!

A considerable economic record of Judaic presence is registered in Treviso in the year 905. The brisk activity of Jewish shops and artisans is recorded in that year as being the generative factor of that city's commerce, a certain indication that they were already well-established at that time. Nonetheless, no other references to what must have been a substantial community has descended to us.

The existence of a variety of such negative or indirect proofs must substitute for the dearth of the physical evidence of a significant, ongoing presence of the Jews throughout the Veneto in those difficult times.

Venice Becomes a Sea-going Nation

The early Venetians, strategically positioned on their cluster of islands for overseas commerce, set out to secure domination of the Adriatic. As we have seen in Fact Paper 29-I, ancient Jewish communities were rooted around the Adriatic shores and were an integral part of a comprehensive commercial network linking the Near East to North Africa and Europe to the West as well as to China and India to the East.5From Trieste down the Dalmatian coast past Ragusa (now Dubrovnik) to Naupoli, and from Padua past Bari to the tip of the heel of the Italian peninsula at Otranto, some evidence of ancient Judaic presence is found in every port of significance.6

The dispersion of Jews into the Diaspora proved to be both a boon and bane, for while the Jews suffered recrimination and repression throughout Christendom, they were, at the time, uniquely able to extend credit to their counterparts throughout the Diaspora. Letters of credit written by Jews in one far corner of the western world would be securely honored by their compatriots in the Diaspora months later in some distant land. Judaic entrepreneurs were inveterate travelers, and family ties at strategic commercial centers provided access to markets where a favorable exchange of exportable goods could take place. Jews provided a reliable commercial liaison to sources within enemy territory as well as within friendly territories The Jews were a literate people. Literacy was indispensable to the conduct of international trade.

Mediterranean trade, Fernando Braudel points out in one of his monumental works on the subject, was dominated from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries primarily by Jews, "because they were to be found everywhere."7 Jewish international contacts were consequently invaluable to Christian regimes upon whose sufferance the Jews depended.

One of the prime motivations for the launching of the Crusades was to displace Judaic and Moslem control of trade in the Mediterranean. Venice, Pisa, and Genoa rose from small provincial city-states to consequential sea powers from the twelfth into the fifteenth century largely as a result of Crusader activity. Much of the Mediterranean commerce of the period was wrested from Jewish hands.

In addition, whole communities of Jews were uprooted from eastern areas by noblemen crusaders and transplanted into their fiefs together with their traditional industries. It is from these populations and from enclaves of Judaic enterprise left behind around the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas, that glassmakers, smiths, silk, wool, and linen producers, weavers and dyers, tanners, jewelers and a variety of other artisans and entrepreneurs were dispersed into the Christian Diaspora.

Thus, one of the Marquises de Montferrato brought glassmakers from the Holy Land to his fief in Piedmont, installing them in the forested mountain area at Altare.8

Thus, likewise, the Norman Crusader Roger II raided Byzantium and North Africa and brought entire communities of Judaic silk-makers and glassmakers to Sicily, then under his rule.9

Venice Acts to Capture Judaic Enterprise

The treatment of the Jews in the Venetian Republic oscillated between religious hostility and tolerance, and between economic rivalry and pragmatic realism. At times the Venetians restricted Judaic activity, even expelled the Jews from the city of Venice. At other times they made efforts to retain them or to entice them to immigrate for economic considerations, and for the skills and technologies to which Jews were privy.

The woolen industry was one of the typically Judaic industries being pursued in the Rialto district. The Council of Ten, the ruling body of Venice, decided to take control of the commerce in wool and textiles. On August 29, 1272. they required that the industry be moved from the Rialto to Torcello, a remote island in the lagoon. An effective government control of the industry was thus interposed between the industry and the Jewish entrepreneurs at the Rialto.

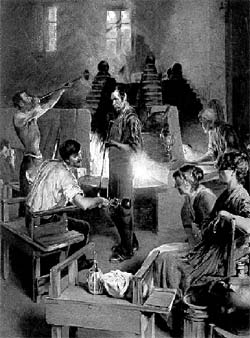

The art of glassmaking was particularly dependent on Jewish artisans. As was shown in HHF Fact Paper 29-I, there are two clues to the ethnicity of the twenty nine charter members of the glassmaker's guild of Venice, the ars fiolaria: Most of the names were of Semitic origin,10 and the glassmakers were firing their furnaces in the Rialto district, the district assigned to the Jews for their industrial and commercial activity.

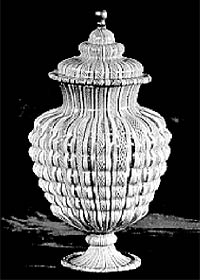

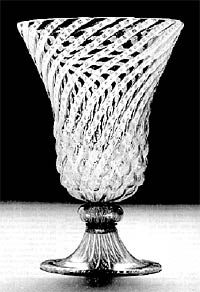

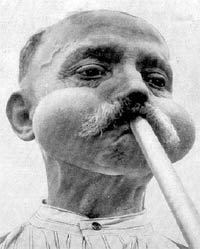

The removal of the textile industry to Torcello proved so effective that, as soon as the glassmaking became a viable industry at the Rialto, the Venetian government took a similar action to gain control of it. In 1292 the Council of Ten removed the industry to Murano, then a cluster of tiny islands out in the middle of the lagoon. The excuse for the move was the fire hazard posed by the glassmaker's furnaces to the crowded city. It is evident that the real reason for isolating the art of glassmaking was two-fold: First, the Venetians strove to keep the secrets of the art of glassmaking from spying governments and prying merchants avid to acquire the profitable industry. Second, they sought to gain control of the glassworking industry and eventually to wrest commercial control of its products from the Jews.

The seclusion of the masters was reinforced by the passage of statutes restricting the movements of the glass-masters abroad and prohibiting them from exercising their skills outside of Venice. Severe punishment, even assassination, was prescribed to insulate the knowledge of the process of glassmaking from leaking to the outside world. "Glass and glassmakers were regarded as a state monopoly and the Council of Ten prohibited both the export of raw materials and the emigration of the glassmakers themselves."11

The assassination of glassmakers who would not heed the prohibition was celebrated by the ringing of all the bells of Murano and Venice, as when a great military victory was won.

The fierceness with which the Venetians enforced their prohibition is dramatically illustrated by the fact that even a Duke of Venice, prior to his becoming Duke and during his tenure as Venice's ambassador to France, was called upon to carry out the murder of a renegade glass-master, which he did!

The burgeoning glassmaking industry in Murano, however, required more glassmakers, and they could not be found in the pagan or Christian communities. The secrets and the skills required for this esoteric craft were still confined to families privy to them, and those families were only to be found where a Jewish community existed.

The earliest surviving records of Murano reinforce the implications to be drawn from the predominantly eastern, even Hebraic morphology of the names of most of the founding members of the glassmaker's guild. Equally convincing is the ethnic character of the names of other participants in early Murano history and the coincidence of glassmaker's family names with those of Judaic communities contiguous to Venice.

The Padua Connection

The Podesta (Mayor) of Murano assumed office in the year 1276. His name was Piero Contarini, a family name that also appears in the earliest surviving pinkasim (minutes books) of the Jewish community of Padua. The journals record that the Contarini family represented the community in many official capacities from the earliest times. A Simon Contarini was one of three persons delegated to negotiate the terms of the establishment of a ghetto in Padua with the Venetian authorities. It was with the assistance of Piero Contarini, and the mayors of Murano who immediately succeeded him, that scores of so-registered forestieri (foreigners) were brought in from the Diaspora at the outset of the development of the industry. Under the aegis of these first officials of the Murano community, over thirty masters of the art are recorded as having come from the nearby, thickly forested areas around Padua from the years 1280-1291. Padua was a major, thriving, center of Jewish life. Even when the Jews were expelled from Venice, they were still permitted to live and work in nearby Padua and Mestre.

There is no mention of glassmaking in the Padovan area in Venetian records.

Nonetheless, the fact that so many founders of the industry in Murano

came from that area leaves no doubt that either glassmaking was being

performed around Padua or that the Judaic artisans, originating from the

Near East where glassmaking remained an ongoing industry throughout the

European Dark Ages, still retained the secrets of the art in Padua.

Jewish surnames typically reflected the towns they came from or the trades they pursued. Eponymous names deriving from towns around Padua are: magister Vaynazo Fiolarus; mayster Marcus de Pianega, maister Jacobinus da Stra; Antonio da Stra; maister Marchesinus Fiolarius; Martini Bergoli; maister Conradus Fiolarius, etc.

Two of the earliest Muranese glassmasters from Padua were Jacobino e Marchesino "de Strata," recorded as owners of furnaces in Murano in the year 1281.12 In 1310, a Jacobellus a vitrisellis, "resident in Murano," is cited in an official paper, "indicating the existence of a manufacturer of beads and of imitation precious stones" (The manufacture and distribution of beads and precious stones were largely Judaic occupations.)13 In the following year, Simeone and Menino de Pienega (a town near Padua) are listed as pro laborius vitreis."14 In that same year, 1311, a Jacobo da Fratina appears in another document that relates the glass industry of Venice to that of Tuscany.15

It should be noted that "Jacob" then was usually, and "Simon" was always the name of a Jew.

This fact is made quite clear when in 1310 a glassmaker, Simeon Brio, cancelled out the distinguishing Judaic name "Simeon" (Simon) on a document; he substituted the Christian name "Benvenutus." In 1316 he returned to Simeon Broio and appears as such in subsequent entries. In 1331 and 1332 Simon was doing business with Bartolomeo Nigro.16 Nigro was also the family name of members of the Padua, Altare, and Genoa Judaic communities.Conversely, many of the family names of Murano glassmakers appear in the journals kept by the Padua Jewish community. The Jews of Padua, albeit they did not suffer expulsion, did undergo a traumatic period. The early records of the community, as well as those of all the communities of the Veneto, have disappeared. That they existed is evident from the fortuitous carry-over of 42 resolutions from what is designated as the "old pinkas" of the Judaic Padua community. The Pinkasim, or minutes books, containing the resolutions were, fortunately, preserved. The dates of the missing centuries and the preservation of a new set of community records match the similar period of four centuries of missing records of the Judaic communities in Altare and Casale Montferrato,17 a hiatus ending with the initiation of a new set of journals by the Jewish communities of both Padua and Casale.

The Padua Pinkasim were edited, annotated and published by the noted Italian Renaissance scholar, Professor Daniel Carpi. These records reflect a parallel pattern of names and origins to that of the names of the forestieri who flooded into Murano in the early period.

For example, provenances which match those of the immigrant Murano glassmakers are included in such cognomens as Iseppe Dalva d'Ancona; Salamon di Zara; Mandolin Trevese; Iseppe Mantoan; Isach Ferarese; Lion de Napoli (that is, the Naupolis on the Dalmation coast); Simon da Coneglian (Conegliano, a town north of Venice, and Treviso have ancient records of a substantial Judaic community). Glassmakers coming from those towns would have had to have been Jews or of Jewish origin, as only the orientali, or easterners, were then privy to the secrets of the art of glassmaking in those towns.

On June 25, 1615, eight representatives of the Jewish community of Padua appeared before the government's ruling body to come to a compromise concerning the payment of unbearable taxes fixed in the terms of their permission to remain in Padua.18 The names of five of these representatives, Simon Catarin, Giacob Moretto, Moise Moretto, Aron de Salom and Finea de Negri, are the same as of families listed in the annals of the glassmaking industries of Murano, Genoa, and Altare.

For example, from 1278 to 1478 the Negri family operated a fornace in Murano, after which the family emigrated to Altare and became one of the original 16 nobile families of Altare, coat of arms and all.19

A most noteworthy Abram Salom is registered in the Ghetto of Genoa as an importer dealing with litharge (lead oxide) for the purpose of glassmaking.20

Cantarin, (transposed to Venetian dialect, or Contarini, as the name is alternately spelled in earlier journals) as was noted above, is the name of a family whose history in Murano goes back to the year 1276 when Piero Contarini became the first Podesta (mayor) of Murano. This event took place 15 years before the glassmaking industry was moved to Murano and five years before the first restrictive statutes were passed by Venice's Council of Ten. It was Piero Contarini, it will be remembered, who first gathered the forestieri from the Diaspora during the propitious period of Venetian tolerance. These were the masters responsible for the development of the industry on that island.

The glassmaking industry grew rapidly in Murano through the fourteenth century, and the rulers of Venice remained fiercely protective of the art. In order to keep up with the burgeoning industry, however, Murano was obliged to continue to draw maestri from Terra Firma in an area encompassed by the cities of Treviso, Padua and Ferrara, well into the 14th centuries,21 and Jewish communities were active in each of these cities.

It is clear that, aside from all other considerations, the mathematical chance of this massive concordance of family names and provenances between noteworthy members of the Judaic communities in and around Padua and those and those of the glassmakers of Murano being accidental is virtually nil. But that is not all!

The Forestieri (Foreigners)

In 1363 the first register appears of a glass-master whose family originated from Mestre, Gerardus fiolarius, filius ser Jacobi de Mestre, habitator Murano. Gerardus fathered two sons, one of whom initiated a family active in Murano until the end of the 18th century.22 Other glassmakers came to Murano from Tuscany (mainly from Pisa, as will subsequently be seen), the Dalmatian coast (Zara, Spalato, Ragusa and Naupolis), Ancona, Treviso and elsewhere. By the year 1350, limiting the account to those whose provenance can be identified by their names or by their application for citizenship, no less than sixty such immigrants were registered in state documents as glassworkers, a substantial portion of all so engaged.Indicative names of masters recorded from other regions having Jewish communities are: Guglielmo Greco (1287, evidently of a family originating from Byzantium); Bartolomeo, pittore di Zara (1290, Zara was one of the towns on the eastern Adriatic shore); Johannes Noenta vitrarius (whose wife was named "Jacoba"), Vivarino fiolario. "Pianega and "Vivarini" were the cognomens of families that became the owners of glassmaking establishments in Murano that have endured into the present, and which have played an important part in Murano history.23

The 14th and early 15th centuries witnessed a steady movement of forestieri into Murano, not only from the contiguous communities but from the Dalmatian coast, Pavia, Ravenna, Tuscany and elsewhere. Dalmatian cities were particularly important provenances of glassmakers and glass decorators. Three Dalmatian coast cities that supplied most of these artisans were Zara, Spalato, Naupolis, and Ragusa, all of which hosted Judaic communities.24

Glassworking is attested in Dalmatian centers as far back as the Roman period. The museums of Zara and Dubrovnik (Ragusa) have significant examples of Roman Period glassware. The ancient involvement of artisans in the vitric arts in Dalmatian cities, whether as primary glass producers or as re-processors of raw glass supplied to them from the eastern Mediterranean, is documented in several contracts preserved in the state arches of Dubrovnik. Such contracts also provide the link between the glassworkers of Dubrovnik and those of Padua and Venice. In 1312, for example, a deed for property in Ragusa was issued to Mafeus fiolarius de Murano, then owner of a furnace in Murano from at least 1311 to 1316. Mafeus also appears in other papers drawn up between 1325 and 1327 in Ragusa. They are conserved in the Dubrovnik archives. In 1332 he is referred to as Matteo (as Maffeo is rendered in the Venetian dialect) of Pianega (again we encounter this town near Padua from which a number of glassmakers went to Murano). The transactions point to the existence of a glassworks owned by the patently enterprising Maffeo. 25

Highly indicative of a Judaic origin extending back to the early Roman period is the registration in the Murano records of 1245 of two glassmakers from Dalmatia who were descendants of former slaves. The name of one, Allegro Schiavo, translates to "A1legro the Slave," and unmistakably identifies its carrier's descent from slaves. The name was a common one assumed by slaves brought from Judah by the Romans. The reoccurrence of such names in the Venetian vitric industry recalls the Aquileian glassmakers whose similar names were molded into glassware produced a thousand years prior to the renaissance of the art in Venice.26

The name carries no pejorative connotations, inasmuch as skilled and highly placed individuals were among the former slaves. Schiavo became the scion of a consequential family of Murano. From its first registration in 1345 Allegro's name appears again in 1360 with those of his two sons. The sons carried on the family tradition, and established themselves solidly into the fabric of the Murano glassmaking industry.27 In 1415 an active furnace was being operated by Donato Schiavo, and in 1416, "Luca and Donato, father and son, of slave origin, are among the artisans of the eastern Adriatic coast who are attested among the glasshouses of Murano." In 1424 the master glassmaker Donato "of Murano" designated "the son of Luca Schiavo," concluded a contract in Raguso to produce glassware in Murano for a merchant from Florence!"28

Another descendant of slaves became an important addition to the Murano glassmaking industry, Giorgio Balarin. "Balarin" translates to dancer. The word comes from the same Latin root as "Ballet." The name refers to Giorgio's peculiar crippled gait. Giorgio's descent from slaves is attested in documents of 1456.29 The name reappears in February 1480: "Giorgio sclavoni dicti Balarin, (Georgio the slave, known as "the Dancer)."

Giorgio nonetheless became the progenitor of an important Murano glassmaking dynasty. "Balarin" is a name "saturating early Murano records." In 1481 Giorgio is identified with an additional nickname as Zorzi Balarin and is again so cited in an action against "Zorzi da Spalato dito Balarin, ZuanTamburlin and Piero Chanar du Spalato." Thus Giorgio is associated with two, evidently Jewish, glassmakers or dealers from Spalato.30

The relationship between Jewish glassmakers and dealers in glass of the Dalmatian cities and Venice continued unabated into the 16th century. In the year 1512, for example, a dispute arose in which a nobleman of Dubrovnik, Marinus Paul de Goze, is accused by Simon da Ragnina of skimming off some of the "glassware and crystal" consigned to another "Simon," Simon de Venise, from a shipment which Marinus was supposed to deliver to the Venetian Simon."31

By the end of the 14th century Venice had succeeded in establishing a firm control over its industries. The state secured a monopoly over the local glassmaking industry through a statutory control of the guild. The Venetian Republic proceeded to reverse its more or less tolerant stance toward the Jews and Jewish presence in Venice became compromised. They were expelled from Venice proper, including the numerous and well-established community on Giudecca. They were forced to join the Judaic communities on near-by terra firma or move out of the area.

Glassmaking did, however, depend on knowledgeable and skillful artisans, so the settlement of forestieri ("outsiders") from the surrounding areas, and particularly from the Padua, continued to the end of the 15th century. At the same time a succession of punitive edicts was imposed to the end of the 16th century to effectively complete the absorption of the industry from the surrounding communities.32

Squeezed by restrictive statutes affecting the entire Veneto, some glassmakers from the neighboring cities accepted the invitation to work in Murano. Other artisans moved west to the Università d'Altare, the glassmaking cooperative that also hosted glassmakers emigrating from Spain. Others filtered out into the Diaspora. During this period, despite the threats of dire punishment for daring to disobey the edicts designed to prevent the exodus of skilled glass-masters, such a movement did take place.

The immediate decline of the industries and the economic loss engendered by the expulsion of the Jews led the Venetian senate to reconsider its actions and again to permit the Jews to dwell and conduct their affairs in Venice. The condition for return was that their dwellings were to be physically separated from that of their Christian neighbors, and that they were to be confined to their quarters at night. On April 22, 1515, a return to Giudecca was first proposed. The Jews made a counterproposal:

The spokesmen for the Jews asked that the Jews be allowed to establish themselves on the island of Murano!33

This pointed request is explicable only within the context of an ongoing Judaic community on Murano, or, at the least - as in the case of Altare - the presence on the island of a community which made Jews, practicing or covert, welcome. The proposal of the Jews was rejected. The first ghetto was established neither on Murano nor on Giudecca but on the contiguous island of San Geralomo. The island was then at the northern boundary of the city. In 1516 the Jews, were still essential for the continuation of commerce and banking, but they were considered expendable for the trades. The largely mercantile community was ensconced within the confines of a huge, fortress-like, defunct cannon-producing brass factory, termed a Geto, in Venetian lingo. It became the eponym of quarter to which Jews were confined.

The Jews were walled into the area with a single door to the outside world. A curfew was imposed and the door was shut tight all night, monitored by Christian guards at the expense of the penned Jews. Thus began a new phase of segregation in which the Christian world drove the Jews out of most means of making a living as artisans, while they continued to make use of the Jews as bankers, doctors, merchants, tax collectors and international credit custodians.

A decree of March 29, 1516, issued by the ruling body of the republic of Venice, the Signoria, indicates that despite the expulsion and subsequent establishment of a ghetto, many professing or covert Jews continued to reside throughout the island complex. The decree demands that Jews "who live in the various districts of the city go immediately to live in the houses of the Geto."

Within a few months seven hundred Jews were permanently housed within the walls of the erstwhile foundry, forming the core of an expanding Judaic population, mainly mercantile, in the lagoon. A largely Judaic artisan population continued to reside in the surrounding communities on terra firma. An influx of Sephardic and Levantine Jews were accommodated in 1541 with the addition of an area adjacent to the Geto; still another contiguous area was allotted in 1603. By that time Polish and western European Jews could also be counted among those with the walls of the ghetto. The population of permanent Jewish residents grew to an impressive 2500 persons, to which a considerable influx of transitory Jewish merchants and travelers must be added.34 By the end of the century the Judaic population of the ghetto alone had risen to over 5000.35

The Ferros and the Pisanos

Two particularly significant family names relate importantly to Murano and Altare and the Judaic communities. They appear, in addition to the four cited above, in the earliest of the Padua records in the persons of Daniel Ferro and Simon Pisano. These two generic family names, one eponymous of a craft and the other of a city, appear ubiquitously throughout Venetian, Altare, glassmaking, and Judaic history, so much so that this intriguing aspect of glassmaking history will be dealt with more broadly on its merits in HHF Fact Paper 29-III.

In that discourse we shall discover how some members of these families left Murano to spread the art of glassmaking through the Diaspora despite the prohibitions the Venetians had imposed, and how others suffered the worst punishments the Inquisition could inflict.

Notes

- HHF Fact Paper 29-I, The Judaic Origin of Venetian Glass , Part I.: The Formative Period.

- HHF Fact Paper 28, The Jews of Aquileia.

- J. E. Scherer, Die Rechtsverhaltnisse der Juden in den Deutschod terreichischen Landern, Lipsia, 1901, 572.

- F. Ugbelli, Italia Sacra Venice, 1717-1722, V, 499.

- HHF Fact Paper 3, The Silk Route, A Judaic Odyssey.

- Attilio Milano, "Gli Ebrei in Italia in Secoli XI e XII," La Rassegna Mensile di Israel, Citta de Castello, 1938, 568-9. Inland cities like Rimini and Bologna are also cited.

- Fernando Braudel, Civilta e Imperi del Mediteraneo nell'eta di Fillippo II, Torino, 1978, 865.

- HHF Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare

- HHF Fact Paper 15, Silkmaking and the Jews.

- HHF Fact Paper 29-I, Ibid.

- W. A. Thorpe, English Glass, London, A & C Black Ltd., 1935/1949, 73.

- Luigi Zecchin, "Cronologia vetraria Veneziana e Muranese fino al 1285, Revista del Stazione Sperimentale Vetro, (RSV) No 1, 1973, 22.

- HHF Fact Paper 20, Ornament and the Jews: Part I - Beads.

- Zecchin, "I Primi Atti del Podesta di Murano," Giornale Economico, 1966, 1109

- Zecchin, "Cronologia vetraria Veneziana e Muranese dal 1302 al 1314 RSV no 3, 1973, 124.

- Zecchin, "Gli'Atti del Podesta del Murano dal 1291 al 1343, GE, XX, Venice, 1966, 1108-9.

- Fact Paper 24, The Jews of Casale Montferrato, and Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare.

- David Carpi, ed. Minutes Book of the Council of the Jewish Community of Padua 1603-1630, Jerusalem, 1979, 437

- Guido Malandra, I Vetrai de Murano, Cassa de Risparmio di Savona, Savona (Italy) 1983, 71.

- Samuel Kurinsky, "Lead-Glass, Altare and Da Costa," Alte Vitrie, II/1, Instituto per lo Studio del Vetro e dell'Arte Vetraria, Altare, March 1989, 22.

- Thorpe, idem.

- Zecchin, "Forestieri nell'arte vetraria Muranese (1348-1425), RSV, No 1, 1981, 17-18.

- Luigi Zecchin, "Forestieri nell-arte vetraria muranese (1278-1348)," RSV, no. 6, Nov. - Dec. 1977. The pattern of eponymous names from communities in which Jewish communities existed continued on past the period above. See Zecchin, Forestieri nell'arte vetraria muranese (1348-1425), RSV Jan. Feb. 1981; Zecchin, "I forestieri nell'arte muranes fino al 1544," GE.

- F. Hamilton, The Adriatic; the Italian Side, 1966, 6.

- Zecchin, "Cronologia vetraria Veneziana e Muranese dal 1332 al 1345 RSV no 5," Sept.- Oct., 1973, 213

- HHF Fact Paper 28, The Jews of Aquileia.

- Zecchin, idem, for further records of the Schiavo family see also "Decoratori di Vetri a Murano dal 1280 al 1480, RSV No. 1, 1977; "Nicolo di Biagio, vetraio a Murano dal 1459 al 1512," RSV No. 6, 1983.

- Verena Han, "Les Relations Verrieres entre Dubrovnik et Venise du XIV au XVI siecle," Annals of the 6th International Congress on Glass, July 1973, 163; Zecchin, "Vetrerie Muranese dal 1401 al 1415," RSV, March-April 1972, and Verrerie muranesi al 1416 al 1425," RSV, May-June 1972.

- C. A Levi, L'arte del vetro in Murano nel Rinascimento e I Berroviero, Venice, 1895 (reference is to a document in which Giorgio is identified as "Georgius Sclavonus famulus ser Menegin Caner,"

- Zecchin, "Giorgio Ballarin, vetraio a Murano tra il XV secolo ed il XVI," RSV, No. 5, 1983, 213-218.

- Verena Han, Ibid, 161, ref: mobilia 25.141.

- Zecchin, Vetrerie Padovane fra il XII andil XVI secolo, RSV No. 5, Sept. - Oct. 1980.

- Carla Boccato, "Licenze per altane concesse ad ebrei del Ghetto di Venezia," La Rassegna Mensile di Israel, March-April 1980, 106.

- Boccato, Ibid, 110.

- Attilio Milano, "Gli Ebrei in Italia nei secoli XI e XII, La Rassegna Mensile di Israel, Citta di Castello, 1938, 648.