Leonardo da Vinci Artist, Humanist, Scientist, Jew[?]

Fact Paper 35

© Samuel Kurinsky and Father Franco Bontempi, all rights reserved

Summary: Report that Leonardo da Vinci's mother was Jewish. Leonardo expressed Amadean precepts through his art, representing St. John as Judaic law, presenting St. John (the Old Judaic Religion) as the path to divine knowledge.

- The Nobility of a Talented Bastard, Leonardo

- Leonardo and the Jewish Tradition

- The Historical Background

- Arianism, Jews, and the Church

- Don Franco Bontempi's Thesis

- Leonardo, a Mysterious Character

- Contact between Leonardo and Judaism

- Leonardo and Amadeo Mendez da Silva

- The Amadean Principle as the Basis of Leonardo's Paintings

- Don Franco's Conclusions

- The Progression of Leonardo's Philo-sophy Through his Art and as Reflected Through the Work of his Disciples.

- Notes

The Nobility of a Talented Bastard, Leonardo

Such was the caption of an article in the important Italian Newspaper, Corriere della Sera of October 1, 2000.

"Recent research maintains," the article begins, "that the maestro of Vinci was born of a Jewess who stemmed from Russia." The article states that whereas the theory that Leonardo's mother was a Tuscan countrywoman remains valid, new evidence opens the additional option that Leonardo's mother was, in fact, a Jewish slave. It was noted, emphasizes the article, that the name of Leonardo's mother, Caterina, always given with no other identification, carried the impression of a simple countrywoman or domestic, if not actually a sort of slave, "probably Jewish of provenance Russia, as was then common in the rural districts." [My italics]

Previous assumptions about the circumstances of Leonardo's birth were based on the reference to it by an anonymous predecessor of the famous biographer of Renaissance artists, Vasari, dated about 1540 and repeated by Vasari and subsequent biographers: "Leonardo da Vinci, cittadino fiorentino, quantunche fossi legitimo figlioulo di ser Piero da Vinci era per madre nato di bon sangue [Literally: "Leonardo da Vinci, Florentine citizen, although he was a legitimate son of Sir Piero da Vinci, was born from a mother of good blood"].

An erroneous interpolation of di bon sangue came into use as late as 1998, when a biographer of Leonardo, Carlo Vecce, repeated that the mother of Leonardo was of "a family of nobility or merchants, impoverished and retired in Vinci."

A solution of the anomalous reference was sought by Professor Mario Bruschi of Pistoia, a diligent explorer of the archives of his city. His recently published Abitanti di Vinci ["The Inhabitants of Vinci"] covers Leonardo's family from the fifteenth century forward. Bruschi proved that, according to the dialect and idioms of the time, born di bon sangue does not signify one born of "good blood" but a figlio del libero amore, that is: a son of free love [that is, "of hot blood!"].

Bruschi states that therefore, the phrase of the sixteenth century biographer has to be more accurately translated: "Leonardo is the legitimate son of Piero [da Vinci] because the father recognized him by giving him his name, but he was nonetheless illegitimate, that is, a bastard, because he was born of a mother not married to his father."

Bruschi cites other examples of the use of this and similar designations about inhabitants of the region. In a register of marriages in Vinci between 1565 and 1575, probably that of Piero da Vinci's descendants, a short list of associated names appears, including Caterina, Antonio, Lucrezia, Lorenzo and Leonardo. While it is not possible to definitively say that this was actually Leonardo's family, two of them, Lorenzo and Leonardo are designated as buon figlioli [literally: good sons], that is, the sons of a buona donna [literally "good woman"]. This is the common reference in the region for one born of an unknown mother or out of wedlock. The designations, bon sangue, buon figliolo, buona donna were not then derogatory terms. Bonsangue, Bonfiglioli and Bonfanti, (that is: bon infanti), descendants of a buona donna, are common contemporary family names, all designating the families of those that were not given the father's name.

The frequency with which such family names occurred, accepted, and were carried on into modern times, make it clear that the norms of the times were not as Victorian as they became in modern times

Leonardo himself gives unequivocal support of the interpretation that he was the product of passionate free love. Leonardo extolled the propitious circumstances of his birth out of wedlock in a paper found in his notebook on anatomical research in the Weimar library. "Leonardo," the article in the Corriere della Sera notes, "now past fifty-one years old, alludes to himself as a product of free love."

"The son," wrote Leonardo, "begot in the worrisome lust of a woman and not from the wish of a husband, soon becomes paltry and of coarse talent. The man who employs coitus with force and uneasiness, produces children wrathful and questionable. But if coitus is performed with great passion and great eagerness by both parties, then the son will become of great intellect and witty and vivacious and loving.'"

Leonardo and the Jewish Tradition

It is well known that Leonardo was born two months after Piero da Vinci took a proper Tuscan bride, and that he was afforded Piero's name and home. What is intriguing about Professor Bruschi's disclosures is that his mother was likely to have been a Jewess, and "actually a sort of a slave."

Bruschi's statement that Jews from Russia were common among the domestic or rural workers of Tuscany, and that their status approached that of slaves, deserves looking into. A new aspect of the Judaic heritage remains to be researched and documented.

Don Franco's thesis was that Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), a rationalist at heart, turned from Christian dogma during the latter part of his life. Leonardo expressed his disenchantment through subtle, progressive changes in the subjects of his paintings. Secondly, in the gradual process of detaching his works from Christian credo, Leonardo reached toward the "Old Testament," to the Judaic concept of free will, and to humanist precepts which were roiling under the surface of church-dominated society.

Leonardo's statement could only be made cryptically. Any Christian, particularly one so renowned as Leonardo, who dared to outwardly express such a transformation would be considered a flagrant heretic. To flaunt such views publicly would be to invite the tortures so exquisitely applied by the Inquisitors.

It is necessary, therefore, to interpolate the metaphors and symbolism of Leonardo's latter works within the existing conditions in order to fathom the Leonardo's intent. This Don Franco has done, and has developed a viable construct of Leonardo's message.

Leonardo was not uniquely iconoclastic; he reflected the current of humanism and rationalism that was gingerly surfacing in the Renaissance. The current had ancient founts, dating back to the outset of Christianity, when it was embroiled in a controversy between the orthodox core of the church and a significant challenge to church dogma, Arianism.

The Historical Background

1: Arianism

Arius (c. 250-336), the founder of Arianism, was born in Libya, trained in Antioch, and became a presbyter in Alexandria. At that time Alexandria was still heavily populated by Jews; they formed the main body of artisans and a significant part of the local and international commercial establishment. The works of Alexandrian-born Judaeus Philo, the Jewish rationalist-philosopher, were still extant, and were even more influential in Christian than in Judaic circles.

Alexandria was geographically removed from the Roman and the Byzantine environments and was seething with philosophical and religious undercurrents. About the year 319, Arius proposed, against the vehement admonition of his Bishop, that Jesus, the Son, was neither co-equal nor co-eternal with the Father, and that therefore there was no Trinity, as the son was not of the same substance as the Father. Arius did not discard all the divine qualities of Jesus; he proposed that Jesus was the first and noblest of all created beings, having been created out of nothing by God's free will. The crux of his proposition lay in his dismissal of the Trinity, a fundamental denial of church credo, one upon which the legitimacy of the church itself could be questioned.

Arius won a substantial following in Egypt, Syria and Asia Minor, and his precepts were seeping into western Europe among the Langobard and other Germanic tribes. In 321 Arius was deposed and excommunicated by a synod of bishops at Alexandria. His influence, however, had spread so wide that in 323 Eusebius, Bishop of Nicodemia and Patriarch of Constantinople, convened another synod in Bythnia, Asia Minor. The influence of Arius had become particularly powerful in that region and the synod pronounced in favor of Arius and contravened the excommunication. Arius then wrote a theological work in verse and prose, Thaleia, a few fragments of which have survived obliteration by the church. The controversy became fierce, and Emperor Constantine convoked the famous Council of Nicaea (Nice) in 325. No less than 318 bishops, and a host of priests, deacons and acolytes were in attendance, attesting to the extreme importance to the church of the issue at stake.

Arius boldly expounded and defended his thesis, but did not prevail. The intense lobbying of the church hierarchy, assisted by the powerful arguments of another Alexandrian, Athenasius, led to the banishment of Arius and two other priests who refused to bend to the pressures applied. Athenasius was rewarded the following year by being appointed Patriarch of Alexandria and Primate of Egypt.

This action did not squelch the influence of Arian precepts. Arius was recalled in 334, but Athanasius refused to admit him to church communion, and the controversy continued throughout the East. Arius went to Constantinople in 336, and his supplication won from the Emperor a commandment to admit Arius to the sacrament. A day or two before the Sunday appointed for the purpose, Arius suddenly died. The followers of Arius accused his enemies of poisoning him, and the circumstances clearly support that accusation. His enemies ascribed his death to the judgement of God.

The death of Arius only spurred Arianism to new heights. The orthodox Homoousian doctrine (the identity of essence of Father and Son), sometimes prevailed, but just as often the Homoiousian doctrine (similarity of essence), gained more influence despite the weight of central church pressures. Arianism was always strong in the East, but now its influence burgeoned in the West. Synods and counter-synods were convened to deal with the controversy.

Julian the Apostate (361-363) and his successors extended full toleration to both sides. Finally, Arianism was extinguished in inner church circles by Theodosian in the East (379-395). In the West, Valentinianus launched a war against the Arian forces, but it was not until the year 662 that the main western holdouts, the Lombards, succumbed.

The principles expounded by Arius were never extinguished; they live on, for example in a modified form in modern Unitarianism. During the intervening centuries, humanistic precepts flared up at various times and at various places. Renaissance Lombardy was one of those places, and Leonardo da Vinci was one of those affected. As we shall learn from the digest of Don Franco's account below, many centuries later, during the time of Leonardo's lengthy sojourn in the heart of Lombardy, Milan , the artist began to reflect in his art a change in his religious perspective.

Arianism, Jews, and the Church

The Jews had much at stake in the controversy. The Arians were more than tolerant of the Jews; they protected the Jews against the malevolent actions of the orthodox church. The fate of the Jews was often decided by the state of the controversy between the Christian factions.

Northeastern Italy provides a good example of the fortunes of Jews trapped in Christian religious turbulence. One of the greatest and busiest ports of the Roman Empire was Aquileia, a city which lies strategically at the crown of the Adriatic Sea, halfway between Venice and Trieste. In addition to serving Rome, it was the port of entry of goods from the East for all of Central Europe up to the Baltic Sea. Aquileia was a stronghold of orthodox Christianity.

The port has by-passed Jewish histories. Not even the Encyclopedia Judaica takes note of the fact that a substantial community of Jews, numbering in the thousands, dwelt and worked in Aquileia.1 A sizable Jewish population is manifested by numerous Hellenized Hebrew names on inscriptions of Eastern immigrants.2 Many of the inscriptions show that the great Roman port harbored a significant Jewish community long before he Christians made themselves felt in the area.3 The existence of a great synagogue is attested by a great funerary inscription of the 3rd-4th century dedicated to the daughter of the head of the elders of the synagogue4.

We learn further about the existence of a great Aquileian synagogue from a denial of Ambrogio in a letter to Theodoric that it was destroyed by Christian arsonists! The event was characterized as "an act of Providence," just as the poisoning of Arius had been characterized.5

The Aquileian Jewish community, composed of former slaves and new immigrants from Alexandria and Judah, flourished so long as the struggle between the orthodox church and the Arians remained unresolved.

Saint Ambrose resided in Aquileia, as did Saint Jerome. It is likely Saint Jerome's Aquileian experience that led him to complain bitterly that the Semitic artisans, mosaicists and sculptors were everywhere, and that glassmaking was one of the trades "by which the Semites captured the Roman world."6

In the ensuing Dark Ages after the defeat of Arianism every vestige of free thought was stamped out in the Orthodox Christian community. Only the Jews remained to question Christian dogma. The persecution and expulsion of the Jews generally followed the defeat of the Arians. The Jews, however, dominated the skilled industries and were essential to commerce, and the pragmatic interests of the feudal lords frequently served as a buffer against the expulsion of Jews from Christian enclaves.

In order to resolve the conflict between the interests of the feudal hierarchy and the church, a new work ethic was promoted by the church. Christian guilds were created, into which patron saints of the industrial arts were introduced. At first only glassmakers were exempt from conversion, for no pagan or Christian glassmakers existed. The glassmaking industry nonetheless declined as Jews sought more congenial climates to exercise their art.7

For the better part of a millennium, orthodox Christianity prevailed in Europe. In Spain and North Africa the translations of classical literature, and advances in humanistic and scientific philosophy continued to impact upon Christian consciousness.

The reaction in Christian circles to the threat of the infiltration of iconoclastic precepts led to such aberrations as the Crusades. The campaign was launched as an attempt to stifle heretical ideas at its root in the Near East. The feudal lords who carried out this charge placed a priority on plunder and commercial and industrial self-interest as much as on implanting the cross. Thus the Norman, Roger II, invaded not Palestine but Byzantium. He carried off the greatest treasure the Byzantines possessed, the communities of silk-making and glassmaking Jews and installed them in Sicily, then under his hegemony.8 The Marquise de Montferrato, who did make it to Palestine to became the "Prince of Jerusalem," exported a community of glassmaking Jews to his Piedmontese fief.9

The Crusades failed to squelch the rising tide of rationalist and humanist thought. The weight of the Crusades fell upon the Jews, who were forced to support the bands of Crusaders as they passed by their villages. "Under the iron hand of Pope Innocent III... a new low in the status of the Jews was defined in 1215 at the Fourth Lateran Council. They could no longer hold public office, employ Christian domestics, charge high rates of interest, or collect anything from the Crusaders."10

In the medieval period the church still considered the world the center of the physical universe, and the church as the center of the spiritual universe. In its attempt to contain rationalist philosophy, the church resorted to blaming the devil for implanting heresy. A witchcraft epidemic ensued, finally legitimized in 1488 by the second papal bull on sorcery, Maleus Maleficum (Witches Hammer).

Such were the times in which Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was born. So were Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) and Martin Luther (1483-1546). Erasmus, considered a humanist in the narrow terms of that day, was born at Rotterdam. After his parent's death he was taken from school and placed into a monastery. It was probably the experiences he sustained during the six years he spent among the monks that made him their bitter enemy. Later he became the secretary to the Bishop, passed on to studies in England and France, and became a Professor of Divinity at Cambridge.

The audacity and incisiveness with which Erasmus attacked the abuses of the kings and church in his works laid the foundation for Martin Luther and the Reformation. Probably his most influential treatise was Colloquia, considered his masterwork.

Martin Luther began

his career as a reformer by objecting to the

sale of indulgences (forgiveness of sins) by the Pope. Luther's indignation

of this shameless traffic led to his denying to the pope all right to

forgive sins. Finally, Luther attacked the papal doctrinal system as a

whole. The culmination of the Reformation in 1530, however, did not end

the witchcraft epidemic; if anything, the followers of Lutheran became

even more involved with Satanism as a mechanism for thought control.

Reformist philosophical currents found expression in other significant ways during the burgeoning Renaissance. The Renaissance itself consisted of looking back to pre-Christian times, when Pagan practice was beginning to be replaced by rational philosophy.

In his Atlantic Codex (fol. 12.v), Leonardo describes the milieu of scholars and scientists among whom he lived. Included are Giovanni Argiropulo, translator of Aristotle's Physics and On Heaven; Benedetto dell'Abaco, Florentine writer on mathematics; Paolo de Pozzo Toscanelli, astronomer, mathematician, geographer, and physician; Carlo Marmocchi, student of astronomy.

Leonardo da Vinci gave expression to the humanist movement which formed the foundation of the Renaissance, and he paid homage to rationalism. He was a staunch believer in science, to subjecting all things to analysis. He characterized science as the "knowledge of things possible in the future, of the present and the past.11

At the beginning of his Treatise on Painting he defined the scientific process as reducing everything to its elements: "If we begin with the surface of a body, we find that it derives from lines, the elements of this surface. But we do not let the matter rest there, for we know that the line is composed of points, and that the point is that [ultimate unit] than which there can be nothing smaller."

Leonardo's conclusion: "No human investigation can be called true science without going through mathematical tests." Leonardo thus was a precursor of the "nothing but," school of science which holds that everything can be reduced to its elements.

Leonardo anticipated Darwin: "Necessity is the mistress and teacher of nature, it is the theme and inspiration of nature, its curb and eternal regulator."

Again and again in his writings, Leonardo attributes the beginning and end of all things to nature: "Human ingenuity... will never devise invention more beautiful, nor more simple, nor more to the purpose, than nature does... She puts into them the soul of the body, which forms them, that is, the soul of the mother... This at first lies dormant and under the tutelage of the soul of the mother, who nourishes and vivifies it through the umbilical vein, with all its spiritual parts, and this happens because this umbilicus is joined to the placenta and the cotyledons by which the child is attached to the mother... The rest of the definition of the soul I leave to the imagination of friars, those fathers of the people who know all secrets by inspiration. I leave alone the sacred books; for they are the supreme truth."12

The sacred books to which Leonardo refers are those of the Bible.

His references to God are typically to God the Creator: "O admirable impartiality of thine, thou First Mover; thou hast not permitted any force should fail of the order or quality of its necessary effects."13

Leonardo draws a distinction between science and art. He held that science serves to amass knowledge, whereas art serves to express the function of the spirit.

- Samuel Kurinsky -

Don Franco Bontempi's Thesis

In his dissertation, Don Franco first refers to Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola (1463-94), an Italian philosopher, as an example of the influences coming to the fore during Leonardo's lifetime. In his youth Mirandola, the son of the Count of Mirandola, attended the chief Italian and French universities. A humanist as well as a theologian, he wrote various Latin epistles, elegies and a series of florid Italian sonnets. His philosophical writings include: Heptaplus and De Hominis Dignitate, the theme of which is free will. The consequences of such an essentially Judaic precept was considered dangerous.

When Mirandola issued a challenge in 1486 to all comers to debate on any of the 900 theses at Rome, the debate was forbidden by the Pope on the score of the heretical tendencies of Mirandola's positions. "The humanistic [perceptions in] the dialogue between Jews and Christians," said Don Franco in his dissertation, "was opposed by Rome, which expressed its opposition in Pico della Mirandola's sentence. The [humanistic] movement, which grew between 1480 and 1520, was banished by the religious fanaticism of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation." Mirandola suffered persecution until Alexander VI, shortly before his death, absolved him of heresy.

Don Franco adds that despite the small number of the supporters of the humanistic movement, and despite the difficulty of propagating rationalism, they nonetheless had a great impact upon western art, philosophy and religious thought throughout the following centuries.

An important aspect of Judaic influence upon the Christian world, Don Franco notes, was the advent of the cabalistic movement. From the 12th to the 15th century, this system of mystical but systematic discipline grew to significant size among the Jews. The mystical and the prophetic aspects of cabalism spread among all social classes and made a deep impression upon Christian thinkers. The perception that the world had arrived at a critical time found its highest expression in Italy. It was in the heart of the Renaissance, Florence, that Savonarola proclaimed the world's end.

Jewish mysticism exalted intellectual architecture. In doing so it provided new symbolisms which artists employed for the composition of their works.

Leonardo, a Mysterious Character

Next, Don Franco examines Leonardo himself, and starts with the paradox that although the artist was eminently at the apex of Renaissance, he was a mysterious character for his contemporaries no less than for historians. He was considered, often without foundation, as indifferent to politics, aristocratic, inclined to depression and to "moralism." He is commonly said to have been be in incoherent and inconsistent, a criticism hardly credible inasmuch as various princes would not have implored for his services if he had appeared inadequate. Francis I, for example, would not have appointed him "king- painter" if he considered Leonardo ineffective..

There is no doubt that his contemporaries considered him inscrutable. His reservedness made the Curia suspicious of him. So much so that they accused him of "necromancy," the black art of communing with the dead. In 1486 the Florentines put him on trial for sodomy, an accusation that led Sigmund Freud to submit his paintings to psychoanalysis, and to attributing some of the deformities of his paintings to his homosexuality.

It is necessary, stated Don Franco, to go beyond the ambiguous appraisals of Leonardo's character and examine the facts about a person who cannot easily be placed into focus. The clearest analysis can be made through his works. The sequence of the subjects is consequential, for through it we can gain an insight into the artist's spiritual itinerary.

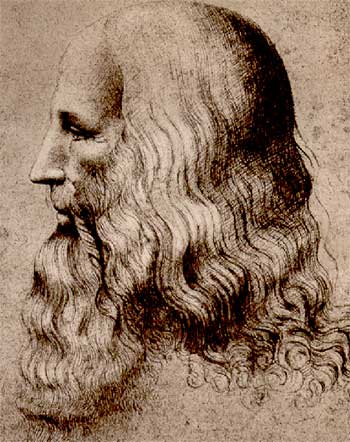

Don Franco lists Leonardo's works in chronological order in order to frame his analysis. They begin in 1470-74 with a depiction of Christ's baptism and end in 1513-16 with a portrait of John the Baptist. The first painting can be dismissed from consideration as it was done as a student in conjunction with Varrochio and Botticelli. His own works therefore begin in 1472-74 with a portrait of "The Pomegranate Madonna."

After allowance is made for the demands of clients concerning subjects and renditions, [of which a documentary record exists], a pattern emerges in which negative and a positive elements appear.

"The first [negative elements] is the absence of the crucifixion and images linked to it, such as that of the blood."

The second is the successive presentation of religious subjects in manner which progressively delineate Leonardo's rejection of Christian credo.

To understand Leonardo's philosophical odyssey from Christian norms to iconoclasm, it is necessary to follow his art through the main turning points in his life. From 1470 to 1482 he is at work in Florence and then in Milan until 1499 at the court of Ludovico the Moor. Although Leonardo "built his vision of the world" within the Florentine environment, it was in Milan that he found more specific answers in his spiritual search. Whereas Florence was the most advanced cultural center at the time, its philosophical perspective was narrow. The Lombard city Milan, from the 1460's, had become the meeting point of several cultures, coming primarily from central Europe. The Lombards, it will be recalled, was the last to succumb to orthodox Christianity. Now Milan had become the main ally of the French kings. In the complex geopolitics of the time, France was antagonistic to the establishment of a state under the church. The church in Rome, however, was attempting to regain its position and control over the territory lost by the western schism.

The position of the French court on governmental separation from the church was reflected in Northern Italy by a relative independence from church authority. The minorities and dissenters took advantage of the liberal atmosphere. The Jews constituted the largest minority, some communities having been resident in Lombardy from Roman times.

Many Jewish communities were established in Lombardy in the 14th century . In the second half of the century Jewish typography was introduced by the Soncino family in Brescia and Soncino. A Yeshiva was established in Brescia. Many Jewish miniaturists and copy workshops of Jewish origin likewise sprung up in the region. These artists had close relationships with the Milanese court, and Leonardo certainly was familiar with them.

The court at neighboring Mantua, under the Gonzagas, had Jewish artists, musicians, literati and artisans as an integral part of the palace court. Some of the Jewish families were privileged with a patente familiari, in effect, granting them the run of the palace as part of the duke's extended court family. Music, performances at the court of Milan, et al was also part of Leonardo's province at Milan.

Between 1499 and 1502, after leaving Milan, Leonardo was in close contact with the Gonzagas at Mantua, and therefore with the Jews of the court.

Contact between Leonardo and Judaism

Don Franco notes that Leonardo had other relationships with Jews, an aspect of his life on which other biographers have placed little relevance. Nevertheless, Don Franco affirms, certain items stand out from the obscurity of this aspect of his life. An observation taken from the Latin version of Savonarola's geometry code appears in a Leonardo manuscript dated 1501. According to the annotators of the manuscript, knowledge of the text is attributed to Luca Pacioli, a Jewish mathematician working at the court of Milan, and one of Leonardo's friends.

Even more significant information is derived from the two Leonardian codices dating to 1503-4 found in Madrid, listing the books belonging to the artist. 40 titles appear in one, and 116 in the other. They include literary, astronomical and mathematical works, the Bible, psalms, and apocryphal works. The translation of these works into Latin, Don Franco points out, were always done by Jews.

Don Franco then adds that Jewish intermediaries was necessary for contact with the Islamic world. It is therefore significant that a letter by Leonardo to the Sultan came to light in Istanbul, in which Leonardo proposes to design a bridge over the Bosporus.

Among the books the artist listed in the codex was "Amadio's book," identified as the life of Blessed Amadio Ispano, printed in Milan in 1476. "Amadio" is Amadeo Mendez de Silva, who wrote Apocalypse Nova. The work aroused much interest; it was even circulated among the cardinals in the enclave where Julius II was elected Pope. Don Franco states that the reading of this work leads to the inevitable conclusion that all of Leonardo's works after 1482 found inspiration from it.

But who was Amadeo? If ever there was a tale stranger than fiction, it is that of the life of Amadeo Mendez da Silva!

Leonardo and Amadeo Mendez da Silva

Amadeo's birth name Mendez is that of a great Jewish merchant family whose trade had spread throughout the Mediterranean. The family ostensibly converted to Christianity in 1420, the date of Amadeo's birth. Amadeo appears to have resided for ten years at the convent of Guadalupe. During this period he traveled to Granada, the last Islamic stronghold in Spain. There some Christians accused him of being a spy.

Amadeo then went to North Africa, justifying his journeys by stating a desire for martyrdom; in reality he was acting on behalf of the King of Portugal.

Amadeo left the Guadalupe convent in 1452, and journeyed to Granada then to Avignon, to Florence, to Perugia, and finally entered the Franciscan order in Assisi. The Franciscans were the most virulent anti-Semites of all the Christian orders, and the "Observant Franciscans" in the order were the most virulent of the Franciscans. They were Amadeo's bitter enemies. Amadeo created such a stir within the order that the head of the convent persuaded the Pope to send him back to Spain. Instead, evidently with the intervention of a Portuguese delegation to Brescia, he was ordered to go to St. Francisco's convent in Milan.

In Milan Amadeo established a solid relationship with the Duke, Franceso Sforza, and with his wife, Bianca Maria. He engaged in diplomatic contacts with France, then at its height in Milan.

He organized an autonomous group within the Franciscan order, and promoted the establishment of Amadean communities throughout Lombardy.

He became acquainted with Francesco della Rovere, who later became Pope under the name of Sisto IV (1471-1484). Amadeo moved to Rome and became the Pope's confessor!

Amadeo's entire thrust as the Pope's confessor was to support the current of liberalization against the machinations of the Observant Franciscans, who were instrumental in expelling Jews from several Italian communities.

During his sojourn in Rome, Amadeo wrote the Apocalypse Nova, composing it as a prophetic revelation made to him by an angel. The literary genre is that of the latter part of the 14th century concerning the end of the world. The revelation does not, however, deal with events but with the meaning of history, and with an perception of the universe. It also follows the ideas of a Franciscan philosopher, Duns Scoto, who places free will at the core of his projections. Scoto was followed byFrancesco della Rovere, a teacher of theology at Padua, the very Francesco who became Pope Sisto IV.

Amadeo's work is in two main parts, the first regarding Amadeo receiving the revelation, the second, entitled Sermones, were small theological treatises attributed to John the Baptist. The form simulates the debates between Christians and Jews, initiated in Paris in the 13th century and carried over to Spain. The text concerns the Bible as it was read in Hebrew and in the Latin Vulgate.

In the part about the Law, Amadeo asks himself if there was a law beyond that of the Old Testament. He answers, "The law is eternal; the rule of God is eternal; the people of Israel are eternal." The task of the Messiah is stated to be the confirmation of the old law.

Amadeo also treats with the subject of Judaic festivals, considered obsolete by the Christians. They are likewise confirmed as eternal, as is the Law. It is emphasized the new law brought by the [Christian] Messiah does not replace the old; both are valid, but the former is the substance while the latter merely adds subordinate details to the former.

These were revolutionary principals for orthodox Catholicism, states Don Franco, and notes that Amadeo goes even further, resolving the controversy about the role of "fear" and "love" in the two theologies with the same "eternal' principle. This somewhat paradoxical thesis, Don Franco points out, assumes great importance in as much as Amadeo was the Pope's confessor! As confessor to the Pope, his influence at the Milanese court was pivotal; it was the influence that affected Leonardo's thought and works.

During Leonardo's extended stay in Milan the iconographic message within a succession of paintings reflected Amadeo's influence.

The Amadean Principle as the Basis of Leonardo's Paintings

Leonardo's presence at the Milanese court in the spring and summer 1482 coincided with the presence of Amadeo, whose life ebbed out on August 10th of that year.

According to Christian theology, Judaism is superseded by the new religion. Amadeo denied this conclusion in two regards:

First, Amadeus takes a cue from the evangelical text, Matthew 11, 13-14, in which John the Baptist represents the old religion and Jesus the new religion. Leonardo, as will be seen, thus represented the two religions throughout the latter half of his painting career

Amadeus thereby regards both religions as on the same level, denying the superiority of one religion over the other, but insists that the new religion derives from the substance of the old. He expresses this syllogism in theological terms by placing Jesus below John the Baptist In the Apocalypse Nova, John the Baptist is given equal honor to that of Jesus. John's birth is given the same weight as the birth that took place in a cave at Bethlehem. Amadeo does not reject Christianity; nor does he present an alternative; his thinking merely carries out his stand on the law: "The substance is the Jewish religion, the new religion is incidental." We are aware that in scholastic philosophy, the substance is invisible, while incidental aspects, size, quality, color and shape are visible. Therefore when a painter reproduces Christian symbolism, he is in reality representing Judaic substance.

Second, Amadeo introduces a radical change in the life of Jesus. Jesus ascends to heaven in Israel from Solomon's temple. In this incarnation Jesus' public life and Crucifixion are completely eliminated. Leonardo found in the Apocalypse Nova a series of images which could be translated pictorially, and he did so.

One must first take note of what did not appear in Leonardo's paintings: Leonardo never rendered a depiction of the crucifixion. Despite the fact that a representation of the crucifixion was virtually a requisite for every artist's portfolio in those times, Leonardo never attempted the subject of Christ's passion.

Women were featured by Leonardo in three contexts: commissioned portraits of aristocratic women; the Madonna and child [or children, as discussed further on]; the Annunciation [the announcement by the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary of the incarnation, of Christ].

The Annunciation

was often painted in the 14th century and was often placed near Jewish

communities. The incarnation account, wherein Mary is told of the entrance

of the divine spirit into her womb, was always the

subject of debate with the Jews. According to the Christians, it signified

the carrying out by a virgin of Isaiah's Messianic prophecy. The Jews

held that the Christian version was invalid, being based on a mistranslation

of the Hebrew word for "girl" into "virgin."

Amadeo's version removes the dispute from Christ's Messianic character to that of simply being born pure. The angel Gabriel in Apocalypse Nova exalts Mary as the seat of wisdom. Woman thereby becomes the source of wisdom, not in its secular sense, but in its spiritual connotation. In Leonardo's pictures, woman occupies the central space, since it is through her that the ascent to heaven takes place.

Don Franco analyzes the Mona Lisa portrait as an example. Behind the woman's head there is a water basin with a river floating under it and the depiction of two paths, one to the left and the other to the right. It is clearly not intended to be a simple landscape background but a metaphoric representation. It is a Cabalistic construction, an exact reproduction of the safirot chart of the Cabalists. The water basin represents the source of Grace which gushes directly from the divinity. It flows down to divide into two rivers to which one gets by the two paths. Thus is represented the concept that the water source flows through many rooms through which the soul passes to arrive at a spiritual wedding with the divinity.

Leonardo's illustrations of John the Baptist are far more significant, for their portent becomes ever more clear from the progression from painting to painting. As noted above, John the Baptist represents the ancient Judaic tradition and is placed above that of Jesus in Amadean philosophy.

Leonardo began his artistic works as a student (as did many other artists), by painting "The Baptism of Jesus." It ordinarily represents the event taking place in a manner according to orthodox Christian theology: John the Baptist knows Jesus as the Messiah, and is depicted in a position of inferiority. This scene does not appear as such in any of Leonardo's works after 1482.

A sketch made in late 1482 in Milan depicts the Virgin with John and Jesus as children. The peculiar aspect of this drawing and its reappearance in that form thereafter, is that the two children are indistinguishable. The painting is thus a clever pictorial transcription of the equivalence of Judaism and Christianity.

Then, in a picture now in the Louvre, the child Jesus is missing and the child John (representing the old religion) is represented by a lamb. In the Christian tradition, the lamb is Jesus who is immolated. By attributing this condition to John the Baptist, Leonardo moves the theological center to Israel. The cryptic statement Leonardo makes in this painting makes the persecuted Jewish people the Easter lamb.

Finally both Jesus and the Virgin disappear from Leonardo's paintings. Only John the Baptist, representing the Judaic tradition, remains. The representation of the old religion in the form of John then evolves to a more direct statement in his latter works. In the Louvre are two paintings from this phase of Leonardo's pictorial evolution. One is entitled "Bacchus" but is actually John the Baptist in the form of Bacchus, and the other is entitled "St. John the Baptist." In both paintings, John remains no longer a second, but the sole subject.

The fact that Bacchus was chosen as a metaphor for John the Baptist demarcates Leonardo's thoughts. Bacchus was considered a guide to spirituality. Tradition has it that after reason is overcome by wine, one's soul can rise to the contemplation of God. In the painting Bacchus (John the Baptist) points to heaven, thus indicating that the Old Law is the sole path to a spiritual ascent. The gesture is repeated in scores of subsequent paintings of the Leonardo school and disciples.

Leonardo executed the latter works in Rome, where he suffered progressive difficulties with the Curie. By that time his written opinions were no longer unknown. Despite his great renown and universal acclaim, no more works for the Vatican were commissioned. He was accused of necromancy. Leonardo left Rome for France.

Don Franco's Conclusions

For Leonardo, a man keen for the most speculative of inventions and the most complex of technological solutions, the main thrust of his intellect was to arrive at basics. At a time when the Christian world was in flux, it was necessary for him to find a dialectic that sustained his concept of the universe. In rereading western cultural history, he found it to be based on Judaic precepts, and that the other two religions, Christianity and Islam, were its spiritual daughters. The demand by Renaissance man for a rebirth of rational society could only be made possible by a return to basics. It should be noted that Leonardo died when the Protestant Reform began. That was likewise linked to the Bible as a basis for Christianity.

The difference between Leonardo and Luther was that the latter remained integral to Christian theology, whereas Leonardo came to consider it a purely external expression. 16th century events imposed Luther's and the Counter Reformation's precepts upon society, while Amadeo's and Leonardo's ideas passed into oblivion.

From the collection of the Brera Gallery, Milan.

The Progression of Leonardo's Philosophy Through his Art and as Reflected Through the Work of his Disciples.

Leonardo earned much of his livelihood through painting, albeit his over-riding interest was science, engineering, and other secular disciplines such as music, philology, architecture, anatomy and medicine, optics, astronomy, botany and mechanics. The church was the main patron of his art, and he was constrained to devote his talents to subjects the church commissioned or deemed suitable. Father Franco Bontempi was struck by the extraordinary pattern of changes that took place through time. Placed against the scientific set of Leonardo's thinking as expressed in his own hand, and against the literature he possessed and influences known to have impacted upon him, Bontempi concluded that a cryptic message was being expressed.

Leonardo was famous and revered in his time. Each of his paintings became a standard for an extensive array of imitators. Much of Leonardo's art is extant, but that which has been lost becomes visible to us through the work of his disciples. Scores of similar works were produced, some of which were so close to the original as to be scarcely distinguishable. Whether the message contained in Leonardo's work was understood by his imitators cannot be ascertained. Whereas Leonardo never inserted the cross in his paintings of St John the Baptist, some of his followers did so, perhaps inadvertently, perhaps deliberately.

Taken as a sequential whole, Leonardo's works make a powerful, albeit cryptic, argument in favor of Father Franco Bontempi's thesis:

Leonardo's humanist iconoclasm sought its roots in Judaic tradition.

Notes

- Yves-Marie Duval, "Aquilee et la Palestine entree 370 e 420," Antichita Altoadriatiche, Aquileia 1978, pp 352-382.

- B. Forlati Tamaro, "Iscrizioni greche e Syriani a Concordia," Antichita Altoadriatiche,, 1978, pp. 383-392.

- Giovanni Brusin, "Orientali in Aquileia romana," XXIV & XXV, Aquileia Nostra, Aquileia, 1953-54, pp. 56-70

- Luila Craco Ruggini, Il Vescovo Cromazio e gli ebrei in Aquileia, Antichita Altoadriatiche VII, 1975, p. 363.

- Ruggini, Idem

- St. Jerome. Comm. "Orbe, Romano Occupato," Exeliel, xxvii, in Pat. Lat. 25, p. 313.

- HHF Newsletter 61).

- HHF Newsletters 52, 54, 56, 61

- HHF Newsletter 51.

- Nathaniel S. Lehrman M.D., "Witchcraft and the Jews, HHF Newsletter 65.

- Cod. Triv., fol.17v/

- Quad. Anat. Fol. 184a.

- Cod. Arund., fol., 24r..